If you know about hanging, drawing and quartering, one of the less delicate methods of execution in Britain then you’ll probably be quite relieved to hear that not every traitor qualified to be hanged, drawn and quartered. But then you find out the alternative.

Death by burning.

Women weren’t hanged, drawn and quartered, so far as we can tell, because in order to cut someone open from neck to groin you have to take their clothes off, and according to William Blackstone "the decency due to the sex forbids the exposing and publicly mangling their bodies".

Basically, because nudity isn’t okay when you’re pulling someone’s intestines out.

However, women could be and were found guilty of treason. After Edward I’s Treason Act of 1351, acts against the king became known as High Treason, which included the counterfeiting of coins. However, it was also possible to commit what was known as petty treason, which meant killing anyone who was seen as lawfully superior to you. This mean that women who killed their husbands were also found guilty of treason and punished accordingly.

The issue became more complicated in Britain in the fifteenth century, when heresy (the religious crime of undermining or speaking against the Church) became a crime that was punishable by burning and enforced by the King’s men. And then even more complicated in the sixteenth, when the monarch became the Head of the Church following the English Reformation, drawing together the two crimes of heresy and treason and making them far more open to interpretation. In Scotland a number of women were also burned as a punishment for witchcraft.

Like hanging, drawing and quartering, though, burning was a horrible death. Bundles of sticks (referred to as ‘faggots’ in contemporary sources, to every history teacher’s joy) were piled around the victim, who was tied to a upright post called a stake. The wood would then be set alight in front of a large crowd, who watched as the victim was reduced to a charred lump.

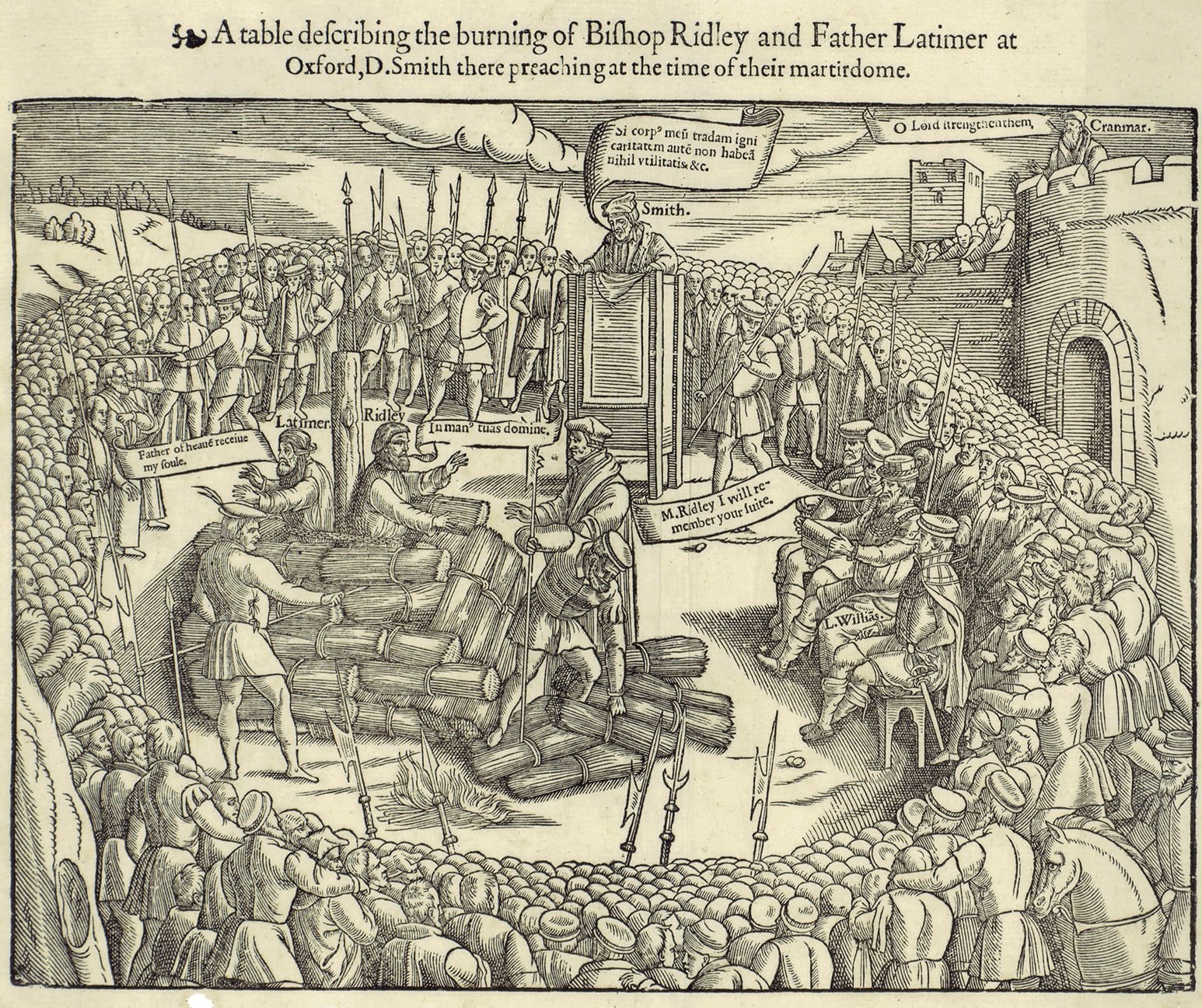

Protestant bishops Latimer and Ridley were burnt as heretics in 1555, during the reign of Mary I. The scene is described in detail in Foxe's Book of Martyrs

Death might come at varying times. Luckier traitors and heretics might suffer a heart attack or die from suffocation relatively quickly, but in other cases they suffered the shock of large-scale burns that were inflicted on their body, and died in incredible pain. In theory, once lit, the flames were supposed to engulf the criminal but this didn’t always happen – sometimes the wood was damp or the fire was badly built. According to Foxe’s Book of Martyrs, at the execution of Bishop Ridley in 1555 the fire “burned clean all his nether parts, before it once touched the upper”. Sometimes well-meaning friends and relatives tied bags of gunpowder around the neck of the victim to bring about a less painful death but as it wasn’t contained enough to cause an explosion, this probably only had the effect of scorching the victim further.

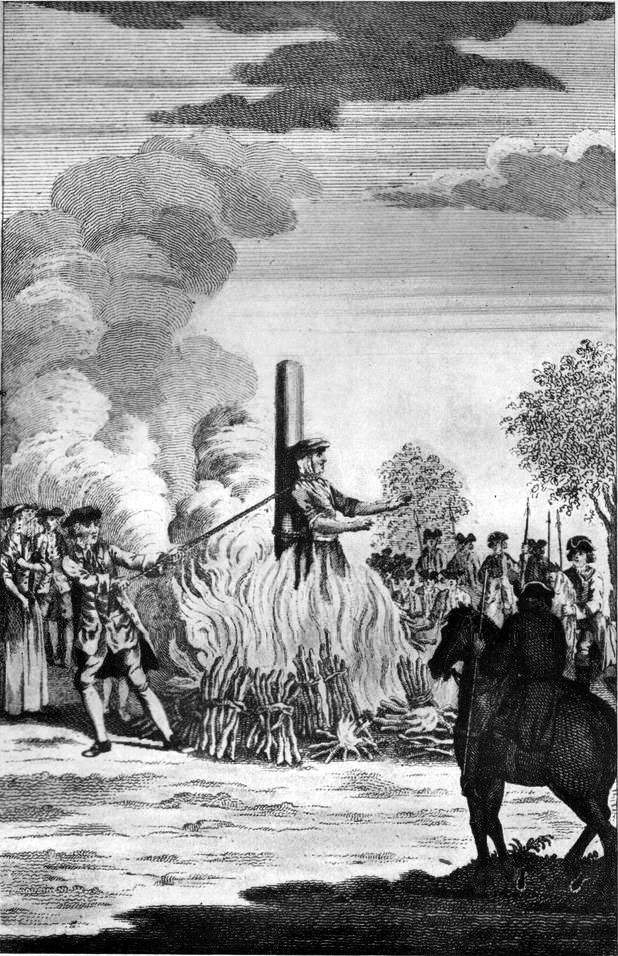

Burning was still a feature of 17th century crime and punishment, but towards the end of the 1600s, it was becoming the practice to strangle the victim – by then generally women – with a cord that was passed through a hole in the stake. This was supposed to be done before the flames reached the body but the success of it was uncertain. At the execution of Catherine Hayes in 1726 the flames reportedly blew onto the hands of the hangman and prevented him from finishing the job. She suffered an agonising death that may or may not have been speeded up by the hangman’s next tactic, which was to throw a large lump of wood at her head.

Catherine Hayes was burnt at the stake in 1726 for petty treason after her part in the murder of her husband. The hangman was unable to strangle her before the flames took hold because they blew back onto his hands, so she experienced great pain until he threw a large piece of wood at her head. At the same execution, one of the stands collapsed, killing two spectators.

As with hanging, drawing and quartering, the taste for really gruesome and painful punishments was waning by the end of the eighteenth century and argument against retribution were gathering strength. The burning of Phoebe Harris in 1786 for counterfeiting caused the Times to state that “man shudders at the idea”, and the Treason Act of 1790 abolished the practice once and for all.

Burning fits into a similar crime and punishment timeline as hanging, drawing and quartering, and sits alongside it as one of the most fearsome forms of punishment in British history. They both occurred most frequently when there was a focus on retribution and deterrence as the aims of punishment, and were used interchangeably at times of great social change to enforce the king’s authority.

But with less nudity.