My PE-teaching career in five massive risks - Part 3

Now, this blog post may shock you a little bit, which is why I thought it might be a nice post to release just before the winter break. I am going to detail below a genuine risk I took in one of my A-level PE lessons in 2013 and a risk that I have repeated ever since. My aim is not to encourage you to take the same risk. In fact, I hope you don’t. But I do want to provoke you to consider what the importance of risks is and how risks may inform and improve our teaching.

Be aware that I have blogged on this theme previously and this is part 3 of this series of posts. Part 1 and part 2 can be read via the links provided.

As you read through this post, I encourage you to consider two things:

- What is the role of risk in the development of your teaching skills?

- What makes things real for your students?

So, without further ado, let’s look at this risk…

Context

| Course | A2 Physical Education Sport Psychology Unit in 2013. |

| Lesson | Group dynamics. |

| Size of group | 18 students. |

| Facilities | PE-specific classroom with sports hall next door. |

| Lesson length | 90 minutes. |

This was an annual formal lesson observation and my observer was a colleague called Jon Marks, who was the Director of Faculty at that time.

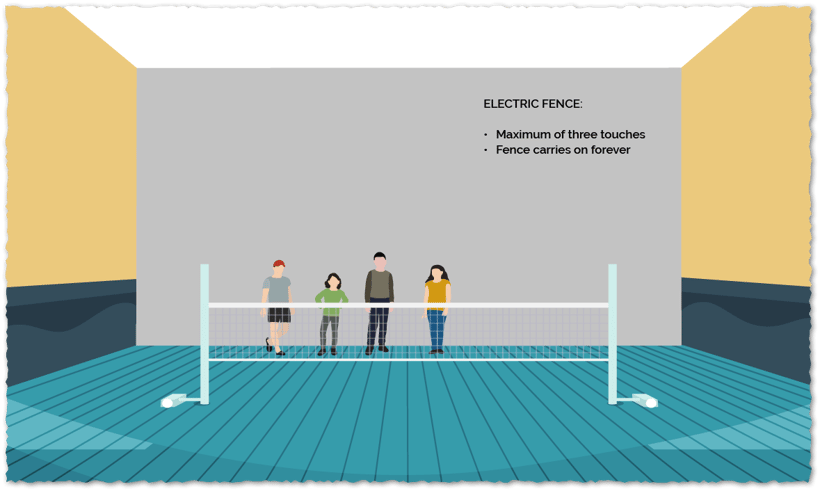

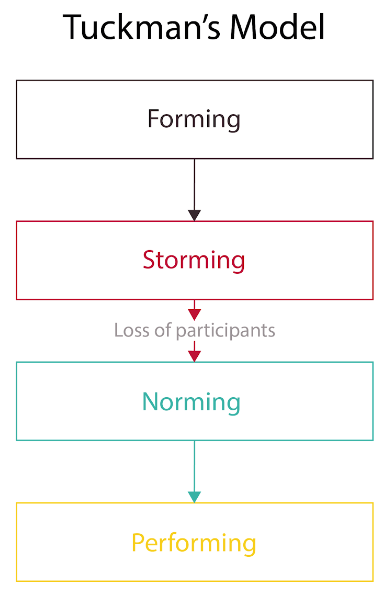

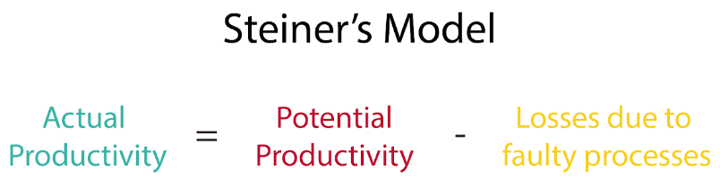

Group dynamics was the aim and in previous years I had taught the theories of Tuckman and Steiner with the classic PowerPoint, worksheet and past-paper-question-type lesson. But in 2013, I decided to take things in another direction. I wanted my class to experience group formation for real. I wanted to give them a challenge that would force them to genuinely solve a problem as a group. I researched outdoor adventurous team-building skills and found the usual challenges: “crossing the acid river” or “escaping the crocodile-infested waters” just weren’t going to cut it and I knew that, with this type of activity, students would be able to opt in or out based on how seriously they took the activity. I eventually settled on an activity called “electric fence”.

In essence, students needed to figure out how to get all members of their group over a height (badminton net) that was just a bit too high to be jumped or easily scaled. But even this activity didn’t feel challenging enough. I wanted something more.

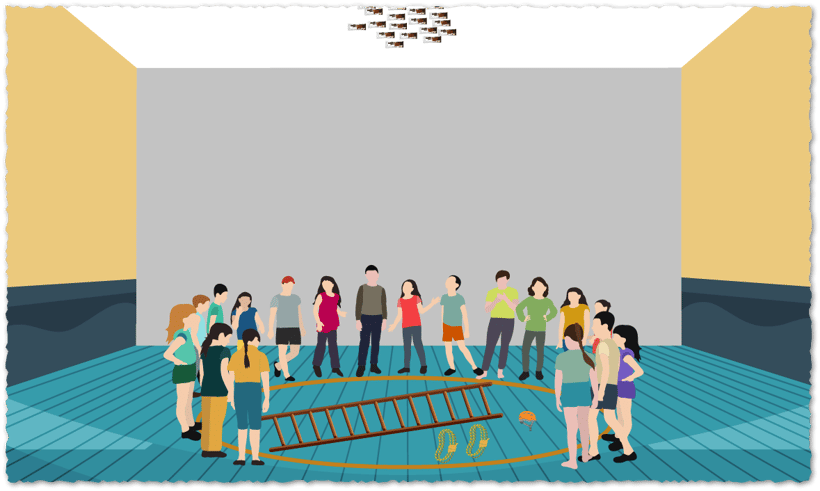

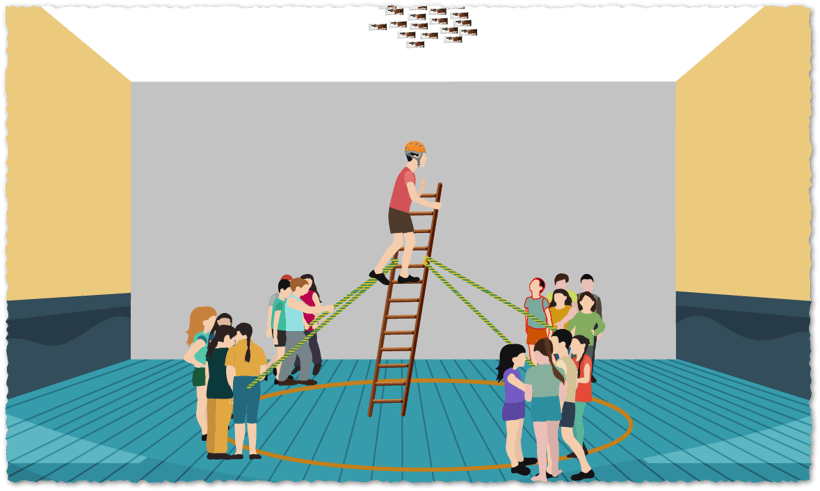

I then had a chance conversation at lunch with a colleague who ran the College’s Duke of Edinburgh scheme. I told him what I was looking for and why and he made a series of suggestions. Once again, I was underwhelmed by the range of offerings, as I didn’t find them “real” enough. My colleague eventually said “Well look, if you want something really challenging, you could make them climb ladders to retrieve a prize.” My ears pricked up and I was intrigued. My colleague, Matt, went on to describe this scenario:

- You need to sellotape chocolate bars or equivalent to the ceiling of the sports hall.

- You need to provide your group with a roped-off circle below the chocolate.

- Inside the circle, you need to provide them with:

◦ A climbing helmet

◦ A free-standing ladder

◦ Two climbing ropes

Matt then guided me that this was the challenge*:

- The students must recover the chocolate from the ceiling.

- Only one group member may enter the circle and, once they do, they may not leave until the challenge is completed.

- All other group members must remain outside the circle.

- The student that climbs must wear the helmet.

- If the group attempts a dangerous solution, the teacher will step in and prevent progression.

*If you want to know how the challenge is solved, please visit the end of this post. To my knowledge, there is only one solution and this is the one that students will inevitably find, often by trial and error.

So, at the start of my lesson, I handed Jon my lesson plan and, unusually for an assessed lesson, a risk assessment too. I stressed to Jon that, unlike during the second half of the lesson that would occur in the classroom, he must not interact with the students during the activity. I also requested that Jon “trust me” as the activity developed.

I then addressed the group and said something along the lines of:

I then introduced the rules of the challenge to them and set them off and the activity began...

I could write many different things about what I observed the group do in the next bunch of minutes but the main one I want to report to you is that, from the group’s perspective, they were not in a PE lesson. Rather, a teacher had set them a very challenging activity and allowed them to progress with it. The usual dynamics of a formal lesson dissolved. The students were in the moment and they debated, problem-solved and, eventually, began attempting solutions.

I genuinely observed the progression of Tuckman’s model of group formation...

...including the challenges that the storming stage brings. I watched as the Ringelmann effect (a faulty process from Steiner’s model) occurred and made notes in order to raise these examples later.

I watched as leadership (the following week’s topic) was expressed and refined. I noticed them looking for external help from me and noted their realisation that they were “on their own.”

Eventually, the group solved the challenge and successfully retrieved the chocolate by sending one student up a robustly secured ladder. As the chocolate was raining down, the group literally whooped and celebrated and, at the very end, when the climbing student eventually got back onto firm ground, the group embraced in a tight, unified team hug.

The lesson then progressed and we returned to the classroom, where I spent 10 minutes introducing Tuckman and Steiner to the class. We then completed worksheets and spent 20 minutes answering a series of exam questions in the pass-the-buck model. As always, the students left with some pre-study homework to complete for the following lesson on leadership and my observed lesson was done.

I received feedback from Jon the next day and he very kindly raved about the lesson. He used terms like “real learning” and “inspirational” and I genuinely believe he meant those things. I agreed with him and I was deeply proud of the lesson. Jon awarded me a grade 1 outstanding lesson grade and life continued as normal.

These days, I always teach group dynamics this way. Whilst specifications change and progress, I find that this experience summarises the key learnings that students need to engage with regardless. Every now and then I bump into a former student in the supermarket or in the pub and they invariably mention this experience to me.

The Solution

Before we reveal the solution below, I want you to consider what you would have done and the solutions that you would have proposed if you had been a member of one of those groups. What does your logic tell you? What role would you have played in bringing the solution together? How effective are you at both productive and receptive communication skills? I ask these questions because this task reveals these skills or deficits intrinsically.

Here’s the solution:

To my knowledge, the activity can only be solved in this way:

- The ladder must be placed directly below the chocolate.

- The rope must loop through the ladder ⅔ of the way up the height of the ladder.

- Tension must be held at all four points of the two ropes.

If this is achieved, the ladder will be very stable and the student will climb the 30 or so feet to retrieve the chocolate safely.

I would like to stress that I do not encourage any teacher to undertake this activity. It is very highly specialised and I am sharing it as an example of taking a risk in teaching, not as the risk that teachers should take.

Thank you for reading the blog. This is my last post before the Christmas festivities begin, so I would like to take this opportunity to wish you all a very merry Christmas or winter break and a happy New Year! I look forward to you returning to the blog for even more PE-specific content in 2023.

%20Text%20(Violet).png)