Why elite athletes dope - A guide for GCSE and A-level PE students

GCSE and A-level PE students typically study a range of issues relating to performance-enhancing drugs (PEDs) in sport and one of those areas of study is why athletes might be motivated to dope. From OCR A-level Paper 3 to AQA GCSE Paper 2 to pretty much all of the equivalent courses, the study of why athletes dope is ubiquitous and, dare I say, the answers that PE teachers (me included) tend to provide our students are quite blunt.

OCR A-Level PE

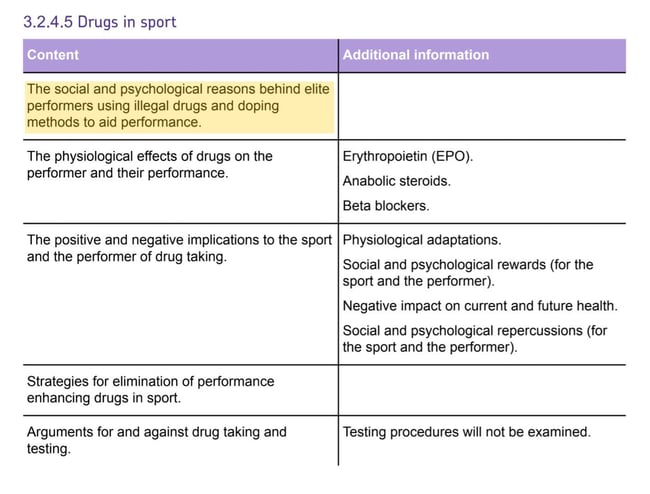

AQA A-Level PE

OCR GCSE PE - Notice the word “understand” in this requirement.

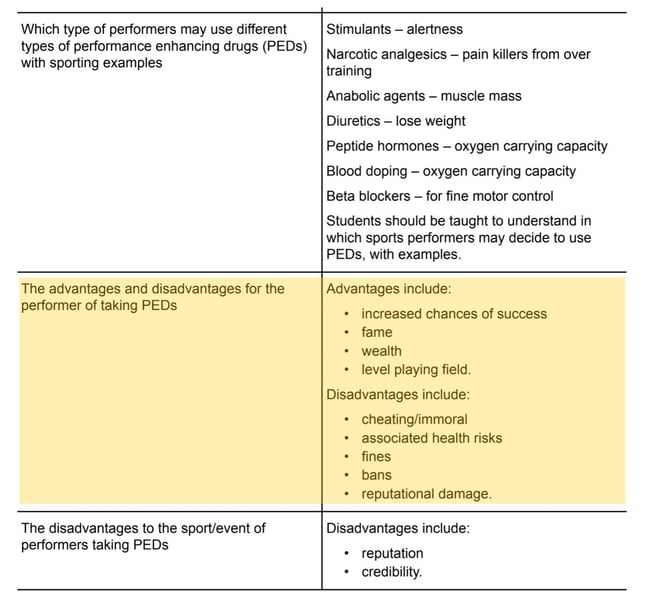

AQA GCSE PE

Edexcel GCSE PE

The thinking goes that there is a finite list of reasons why a performer will dope. If, for example, we take the accepted answers from one exam board, we can see how blunt a response is expected by our PE students:

This image shows the answers that would be marked correct by OCR for their A-level PE course. The content above could be described as AO1 and students may be asked to provide application for this content to be elevated to AO2.

This image shows the answers that would be marked correct by OCR for their A-level PE course. The content above could be described as AO1 and students may be asked to provide application for this content to be elevated to AO2.

I believe athletes dope in elite sport for these five reasons in addition to the generic guidance expected of students on our PE courses:

- The wolf

- It works

- The equation

- Politics

- Performance-enhancing lifestyle

- The structure of lies

Let’s take each one in turn.

1. Reason for an elite athlete taking a PED: The wolf

Throughout our culture, archetypes prevail. An archetype is a prevailing idea that embeds itself in culture via thought, behaviour, representation and that often is supported by representations in literature and film and storytelling in general. One of the greatest archetypes in our society is the idea of the good person and the bad person. Every superhero movie is based on this, right?Fundamentally, we believe that if a person behaves very poorly, it is caused by being a bad person. Likewise, if someone behaves particularly well, it is because they are a good person. This is a simplistic and, as far as some overarching structures are concerned, a functional way to think about the world. People and their approaches to life can be categorised. An athlete who chooses (notice the verb to choose - I’m going to come back to this) to dope is pretty likely to be a bad person and needs to be ostracised. Right? Well, maybe. Rather than stating whether I think this is right or wrong, I want to try a thought experiment, just for a moment.

Let’s imagine, just for the length of these paragraphs that the archetype that existed in our society was not one of good person and bad person. Let’s imagine that the archetype was a clear acknowledgement that every person on earth is capable of behaving for good and behaving for bad. This is the wolf analogy.

Let’s imagine that inside every single person on earth there are two metaphorical wolves. One is warm, fair, generous and kind. The second is aggressive, selfish, loathsome and mean.

Now, let’s imagine that in every person, only one wolf can be dominant. Imagine that the wolves fight each other for supremacy and that this supremacy then emerges through the individual's behaviour.

Now, let’s imagine that in every person, only one wolf can be dominant. Imagine that the wolves fight each other for supremacy and that this supremacy then emerges through the individual's behaviour.My question to you is this:

Assuming that the reason for supremacy is the same for everyone, which wolf would thrive and which wolf would become superior to every single one of us?

The answer, of course, is very simple. The wolf that dominates is:

The one we feed.

The wolf metaphor is a really useful one for challenging the idea that dopers are bad and clean athletes are good. This, in my opinion, is overly simplistic and not helpful. Rather, if we ponder that all athletes have the capability to dope or be clean, we can start to consider some of the factors that might drive behaviour.Now, let’s step back and look at our culture (in other words, at what is feeding our wolves). Society certainly seems far from fair for everyone. There doesn’t appear to be a particularly level playing field. There appear to be structural advantages for some people and structural disadvantages for others. Meanwhile, seeking advantage for personal gain seems to be pretty commonplace and, in wider society, many people behave with a win-at-all-costs mentality at least a lot of the time.

In fact, I would argue that the levels of cheating and doping in sport are far lower than cheating could be cited in our wider society. In other words, it can certainly be argued that our culture, at least to some degree, certainly feeds the loathsome, aggressive wolf inside all of us.

Furthermore, our sporting culture also seems to value –and maybe even overvalue– the winner. Think about the sport you follow and/or play most commonly. What matters most in that sport? As a follower of men’s elite football, I can certainly recognise the fetishisation of winning as the only reason for happiness and satisfaction. In this context, I can find myself feeling pleased that the opponent’s best player can’t perform against my team due to injury or having bias when it comes to officials’ decisions. I learn to value winning more than anything else. Or, at least, I could.

Perhaps there is another point to make here, too. Sport as a whole, at least in its traditional structures and ethos, is one of the remaining bastions where the kind, fair wolf can and is fed more. Through sport, young people learn respect, fairness and honesty. But, as sport moves more towards a commercialised, entertainment-driven series of professions, is it predictable that the loathsome wolf in us all will be fed more? Yes!

2. Reason for an elite athlete taking a PED: It works

Doping is effective. That’s the long and short of it. In certain circumstances and in certain sports, doping dramatically improves athletic performance.I would like to draw a line here. Doping is particularly helpful in sports where physical prowess is far more important than skill. Doping is not (yet) particularly helpful to make a hockey player, say, more skilled in their passing or dribbling, but doping can definitely help in sports where success and failure are more focused on how much force is applied against a resistance.

Let’s take road cycling as our example. Is it any wonder that road cycling (and specifically the grand tours in France, Italy and Spain) has probably seen the most doping in any sporting arena? No! Doping has historically been prevalent here because the sport of cycling is, ultimately, based on how much torque can be applied to those cranks. I am not arguing that elite cyclists are not skilful. Of course, they very much are. But the major influence on winning and losing is power-to-weight ratio over time. Yes, a Tour de France cyclist needs to have great riding technique and the reactions to avoid crashes or rapidly descend a mountain, but the requirement for skill is nowhere near the level of influence of our hockey player example. Hockey players are effective directly because of their skill performance. Yes, speed and stamina help, no doubt about that, but skill will be the deciding factor for elite players.

So, on this point, we actually have two considerations:

- Doping works.

- Doping is particularly helpful in sports where success or failure directly results from the amount of force that needs to be applied, potentially, over a long period of time.

3. Reason for an elite athlete taking a PED: The equation

So far in this post, I have touched on many points that relate to this next one. I have touched on the culture and fetishisation of winning. I have mentioned commercialisation, too, for example. But for point three, I want to bring an idea to the front and, I believe, it explains why doping has always existed in sport and will always exist in sport in the future.I argue that whenever the following situation occurs, doping will be part of the overall picture of elite sport:

Very highly motivated individuals x Extremely high rewards for winning

It is my contention that when these circumstances prevail, doping occurs in sport. This doesn’t mean that everyone will dope. Far from it. But, when we create this culture in our sporting environments, doping will occur.4. Reason for an elite athlete taking a PED: Politics

There have been countless examples historically that tranches of elite athletes will dope or be doped for political gain. In more recent times, it would appear that the state of Russia undertook a rigorous state doping programme before and during the Sochi Winter Olympic Games in 2014. Why would the Russian state in 2014 choose to do this? Why have many other states done similarly in the history of elite sport?The answer to this is politics. Being superior in sports like skating and skiing on the world stage led to an image of success and glory for Russia. It built a sense of patriotism and national pride. It developed a sense of legitimacy for Russian leaders who could, in essence, claim “The system works. Look at our gold medals.” Now, I don’t know enough about Russian geopolitics to be confident that the successes in 2014 directly justified Russia’s invasion of Crimea in 2015, but it certainly would not have harmed these intentions.

Recently, and historically, one of the greatest drivers of elite sport doping is politics, and whilst we must ensure that individuals are treated as individuals in sport, we must acknowledge that doping, and ultimately winning, benefits much greater entities than the athlete alone. Politics and the political climate are definitely a reason why elite athletes dope.

5. Reason for an elite athlete taking a PED: Performance-enhancing lifestyle

Elite athletes in the UK and in most of the world follow a performance-enhancing lifestyle. Athletes on the UK’s podium or podium potential programmes spend their entire training day (and day in general) trying to maximise their performance. It is worth remembering that many, many substances and chemicals happen to be legal in sport and that what makes a PED a PED is not that it is a chemical, nor that it enhances performance, but that it has been selected as illegal.Now, please do not interpret that I am arguing for steroids, EPO or HGH to be made legal. Absolutely not. What I am suggesting is that athletes, as a matter of duty, maximise and enhance their performances right up to the line of legality. An elite swimmer enhances their performances through diet, training, sleep, technology, legal chemical enhancement, etc., and it happens to be that the “other” methods are illegal. One form of enhancement is right, ethical, even expected, but the other is illegal and the source of condemnation. Furthermore, the line of legality does change. Take caffeine, for example. Until ten years ago, caffeine was banned above certain levels in the body, but it is now not recognised as an illegal PED by the World Anti-Doping Agency whatsoever. Caffeine definitely enhances performance in numerous sporting disciplines, is addictive and does have long-term health implications. Yet it is completely legal and, presumably, athletes use caffeine in significant quantities to enhance their performance. In other words, athletes live a performance-enhancing lifestyle, and we should not be surprised that in the hyper-competitive world within which they exist, flourish or fail, they push as close to that line of legality as possible on a very regular basis. Some athletes, inevitably, spill over that line, dope and get caught. Perhaps, I am arguing that every single performance-enhancing behaviour and process that an elite athlete follows is a potential “gateway step” to illegal PED use.

6. Reason for an elite athlete taking a PED: The structure of lies

I’ve thought about this aspect a lot. Lies have a pretty specific structure to some athletes. If we remain in the realms of PEDs for the purposes of this post, I honestly believe that the first lie is, by far, the most important one. Once an athlete spills over the line into illegal doping, they are in a very bad position. They have lied, probably to their families and friends as well as to the sporting world, and once that lie is told, it must be incredibly difficult to go back on that lie.I like to think about this concept with regard to, perhaps, the daddy of all doping stories: the Lance Armstrong case. To young people today, what happened with Lance Armstrong and his teammates must seem like very ancient history, but I honestly feel it is worth dwelling on here. Lance Armstrong won seven consecutive Tour de France titles and doped during all of them. Meanwhile, as his star rose in the world of US-based superstardom, Lance Armstrong became an author, cancer survival advocate, founder of Livestrong organisation and a cultural icon. Whilst I do not want to review the entire Lance Armstrong case, I want to encourage readers to think of one moment in his life that must have happened.

Lance Armstrong left the USA for Europe in his early twenties. I am not going to argue he was a sweet, balanced guy - I mean, I’ve seen the documentaries, and he wasn’t. But he was clean. He arrived in Europe to compete in a sport that everyone acknowledges had a very serious problem with systemic doping. At some point in the weeks and months that followed, he would definitely have had a moment when he needed to tell the first lie. I’m not even talking about his first decision to dope. I am talking about the first lie. Perhaps it was when a journalist asked him a question, or when a friend asked him what was going on with all these drugs or when a competitor asked his advice. At some point, Lance chose to lie, and once that lie was told, a path in front of Lance was created. Yes, the path had many forks and choices in it, but the structure of lies meant that Lance was expected and chose to lie forever.

Within this situation, I can understand why Lance told many more lies. I can understand why he was vehement in these lies. The structure of a lie will do this to you. In Lance’s case, I believe that the stupid, immature, young man he was made a choice, and he chose to lie. He then chose to exaggerate and, perhaps, even justify this lie with more lies and the lie grew and grew and grew and became uncontrollable.

Please do not interpret that I am arguing that Lance’s lies were right. He made extremely grave choices and he was utterly wrong to do so, including all of the bullying and personal lies that he told to cover up the first lie. What I am saying is that lies are dangerous things with lives of their own and, once you tell that lie, it is very, very difficult to simply own up to it, especially when one’s professional credibility is based upon it.

Conclusions

So, there you have it. A few additional ideas to discuss with your students.By way of intrigue and perhaps giving you a simple kick-off point for a lesson on the reasons athletes dope, I encourage you to consider an Agreement Circles activity utilising the following introductory statement:

“All athletes have the capability to become dopers. It just depends on the circumstances.”

This should help you to elicit some interesting responses from your group.

If you would like to learn more about different questioning techniques in the PE classroom, please visit our PE Teacher Academy pages for more information on how to enrol.

Thanks for reading.

James

%20Text%20(Violet).png)