Ten Principles of my GCSE PE Classroom Part 2

In last week’s post, I detailed the first five principles by which I operate my GCSE PE classrooms. These principles are non-negotiable and form the fundamental basis by which I work. In part 2, I aim to develop these ideas and share with you a complete picture of how I manage my work.

My Ten Principles

In last week's blog:

- The classroom is for learning more than it is for teaching.

- Student academic/exam “ability” is unknown and unknowable.

- It is inappropriate to “teach to the spec”. My role is to teach to the breadth of a potential mark scheme for the specification.

- High-quality homework is essential.

- PE classrooms must focus on skill development via the taught content, not the other way round.

In this week’s blog: - All PE content is taught through application rather than being taught and then applied later.

- Feedback must be received as soon after the learning/assessment activity as possible.

- Data comes in three tiers and tier 1 and 2 data is live and volatile and available continuously.

- Students work towards specific targets at all times.

- Every learning activity is diagnostic, with the exception of the final, external exam.

Principle 6: All PE content is taught through application rather than being taught and then applied later.

PE courses - whether GCSE, A-level, BTEC, OCR National, etc. - require students to apply their learning to movement. This is what marks our subject out from biology and chemistry. Our subject is applied and this is a good thing. Application makes a subject domain real. It allows a student to immediately improve their own movement as a result of an improved knowledge base.

PE students should feel connected to their learning. They should feel connected because their learning relates to them and to their experiences.

I also teach biology and, sometimes, feel frustrated at the lack of real-world application that my students can make. This is exactly the opposite to PE, which is inherently applied.

For these reasons, I believe that all teaching should be applied from the outset. Let’s take a very basic example and consider aerobic and anaerobic energy release. Many teachers will focus their teaching on equations and will teach something like this on a whiteboard or via a PowerPoint slide:

Or this…

Our focus is on teaching an equation rather than the application of that equation.

If, for example, we start our teaching differently and examine the shared characteristics of marathon running, race walking and endurance swimming (long-duration and moderate-intensity) exercise, introducing students to how the majority of energy is derived, is much more meaningful:

Beyond this, our teaching can focus on the use of glucose (reactant) before, during and after aerobic performances; how oxygen (reactant) is supplied to the muscle; or how water and carbon dioxide (products) are removed as well as considering whether this system is sufficient to power these performances entirely. This is applied teaching and allows the students to place their new learning in a range of contexts.

I urge teachers to abandon long series of slides that focus on content and, instead, to focus their teaching squarely on application first.

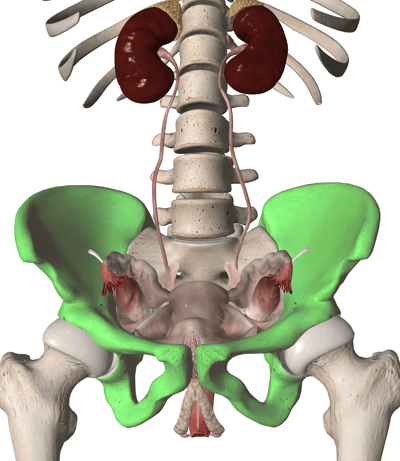

With this in mind, I wish to share one more simple example of teaching with application. Many of you will have taught the location of the pelvis as part of the GCSE. In other parts of your course, you will also have taught that a function of the skeleton is to protect vital organs. For this reason, as you introduce the pelvis, consider using an image such as this one for clear application to one of the functions of the skeleton:

This image clearly shows the location of the pelvis but also emphasises one purpose of the pelvis which is to protect the reproductive organs during sporting performance.

Principle 7: Feedback must be received as soon after the learning/assessment activity as possible.

There is no surprise to this one: learners learn more when high-quality feedback is delivered shortly after the learning episode. As classroom-based PE teachers, we need to recognise this fact of learning and adjust systems to achieve the best timing of feedback possible.

Now, we also need to be realistic and accept that a sustainable way to achieve this is not a teacher spending tens of hours a week marking. Rather, good systems need to be developed to focus the teacher’s limited marking time on the most impacting activities.

In order to address this, it’s useful to consider the three types of feedback we might give:

- Corrective (right or wrong)

- Directive (why/how right or wrong?)

- Epistemic (what would be the impact on an answer if a variable were to be changed?)

These are the three types of feedback our students might benefit from. But, more crucially, the sooner they occur, the more impacting they will be. For this reason I strongly advocate for the use of the following systems where possible:

- Shifting classroom tasks, worksheets and Q&A to online activities, including quizzing and retrieval practice. PE classrooms currently operating without the benefits that automatically marked quizzing with feedback provide are missing a key opportunity.

- Shifting homework assignments to include more auto-tracked and marked experiences, including educationally tracked videos, auto-marked tests and checkpoints.

- Use of diagnostic exam tools such ExamSimulator, which provide not only rapid feedback but auto-generated diagnostics.

- Peer marking for manually written tasks and papers.

- Self-marking for manually written tasks and papers.

What must not happen is either or a combination of the following:

- Little feedback received with delays in feedback reaching the student.

- Teachers attempting to manually recreate the impact of the points made above. This is not sustainable

So, for learning to be impactful feedback needs to occur as immediately after the learning episode as possible.

Principle 8: Data comes in three tiers and tier 1 and 2 data is live and volatile and available continuously.

Firstly, I would like to summarise the three layers of data:

| Tier 1: Observational data | Tier 2: KPIs | Tier 3: Timely assessment | Tier 4: Historic data |

| Time management (attendance) | Quiz scores | Fortnightly checkpoint diagnostics | End-of-unit results |

| Time management (punctuality) | Practice-exam question scores | Core assessment diagnostics | Mock-exam results |

| Time management (deadlines) | Tutorial completion data | National mock exam diagnostics | Exam results |

| Levels of concentration in class | Worksheet completion and scores | ||

| Engagement | |||

| Effort |

I urge all readers to notice that success in tier 1 is highly likely to lead to success in tier 2 and so on. I also urge you to notice that if our primary data stream is tier 4, the behaviours that have led to either positive or negative outcomes in this tier have already occurred. In other words, the data in tier 4 is historic and, typically, redundant. I also urge you to notice the use of the word diagnostics in tier 3. The aim of our tier 3 activities is diagnostic so that this can inform next-step behaviours in tier 1 and tier 2. I will write more about this principle a little further down this post.

Consider what would happen if one’s systems focussed squarely on tier 1, 2 and 3 data. Take tier 1: what would happen if the majority of a teacher’s time was spent facilitating these behaviours? Rather than a teacher spending a large volume of time delivering material, could a teacher shift their behaviours so that their time is spent guiding, supporting, facilitating and monitoring? If so, could the proportion of classroom time spent with students in deep concentration be ramped up? Could the teacher monitor engagement and effort more consistently? Could they spend more time in direct conversation with individual students about why their time management (deadlines), say, has decreased?

But I would like to finish this section with a very clear statement: if a PE teacher completes a tier 4 assessment such as a mock and the results are disappointing, the data indicating that this was going to be the case was available to them weeks and months prior to the mock. In order to be “disappointed by mock results”, the behaviours that have caused those performances have to have been missed or ignored for a substantial period of time. The data points leading to the poor mock results were available in tier 1, 2 and 3 throughout our experience.

Principle 9: Students work towards specific targets at all times.

I will get straight to the point on this one: I strongly advocate for a mastery model of learning. In practical terms, this means that the target for every student on every task is mastery. Now, we can all define mastery differently but my personal and practical definition is the following:

Therefore, every task that I set my students needs to have a clear standard to it. It needs to be a target.

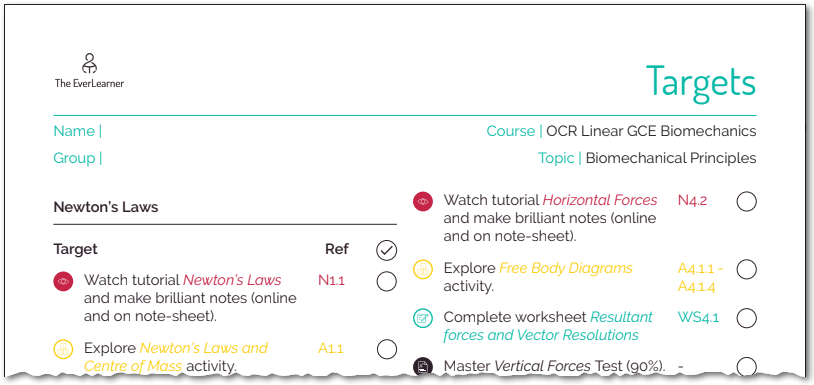

Take a look at this example below. This is the standard targets for the entire unit of work for the Biomechanics section of OCR linear GCE (A-level) PE (click to download a PDF copy):

The core activities for developing the knowledge and skills related to this area and clearly established from the outset. Furthermore, by establishing these targets, I immediately hand responsibility for the learning to the student. Consider a student attending my lesson on biomechanics. They are not able to simply “turn up” and wait for me to tell them what to do. They are the agents. I have expressed to them clearly what my expectations are and it is for them to achieve these targets whilst I spend a big proportion of my lesson time focussed on tier 1 and tier 2 data from above.

Within teaching, I see a dramatic absence of these types of expectations. This is not necessarily a comment on PE teaching but on the general assumptions we make about classroom learning. Too frequently we take the decisions away from students. We direct them. We have them all doing the same thing at the same time. We assume that they are not responsible for their own learning. Why? Let’s assume we are referring to KS4 learners. Students at age 14 to 16 absolutely can take agency. Moreover, when they are given agency, they typically thrive. This is not a woolly notion of “letting them get on with it.” No! It allows me my classroom time to be monitoring their exact behaviours and progress in line with tier 1 and tier 2 data. I’ll put it another way: at age 14, the vast majority of human beings are *biologically capable of producing offspring. So, nature has determined that by age 14, human beings are capable of a great responsibility. I’m pretty sure nature would not have got it so wrong that 14-16 year old students in the UK are not capable of being responsible for learning targets. They are!

*As you will realise, this statement is not an advocacy for teenage pregnancy. It is an attempt to emphasise what young people are capable of when provided the relevant circumstances.

Principle 10: Every learning activity is diagnostic, with the exception of the final, external exam.

If you have read both posts to this point, this final principle will not surprise you. Learning experiences always produce data and, if this data is captured, it becomes diagnostic.

Ask yourself these questions as examples:

- What is your cohort’s/group’s/individual homework completion percentage?

- Which area from the musculoskeletal system, say, does your cohort/group/student struggle on most?

- Which exam command words does your cohort/group/student perform better and worse on?

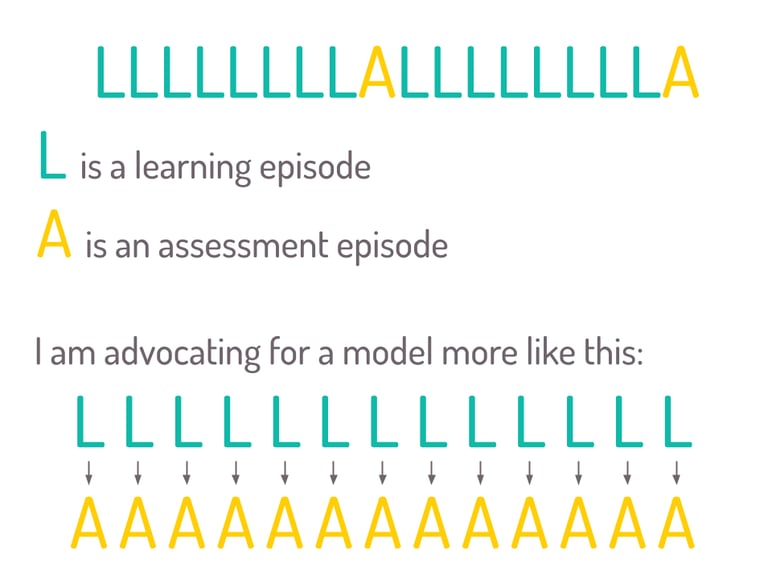

Whilst we can diagnose many other things, these questions will get us started. The main assumption that I would like to challenge is that learning and assessment are separate experiences. Most classrooms operate like this:

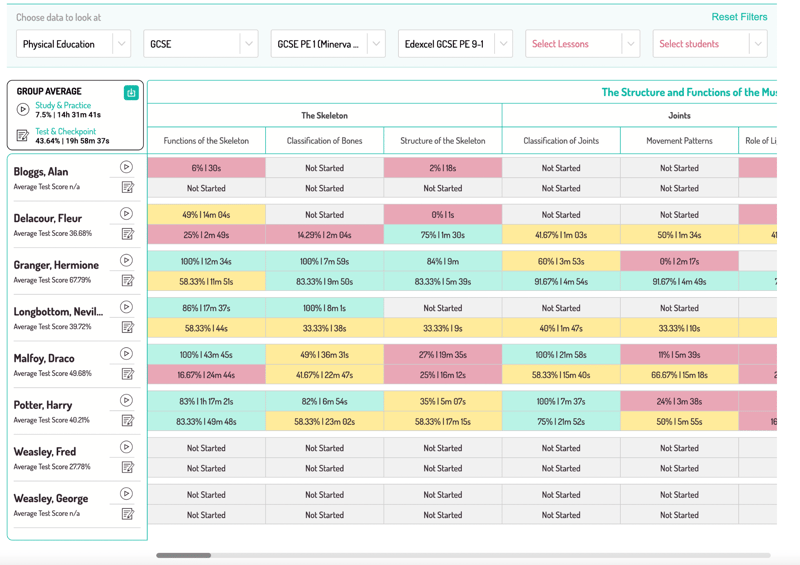

Where every learning episode also is a data point. Here are some visual representations of this methodology:

This image shows four data points for every student, for every lesson. The data points are:

- Tutorial completion percentage.

- Time spent practising questions from the lesson

- Live test score (quality of their most recent 12 answers)

- Time spent testing under time-restricted conditions

Can there be any doubt that Harry Potter is more likely to answer exam questions more successfully than George Weasley on the Functions of the Skeleton topic? Can there be any doubt Draco Malfoy has worked really hard on Functions of the Skeleton but is struggling? Can there be any doubt Neville Longbottom needs to spend more time completing test questions on all of his lessons? Can there be any doubt that Alan Bloggs is a disengaged student and action needs to be taken?

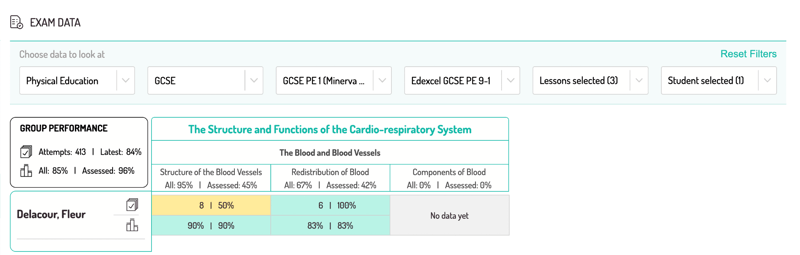

Let’s take another example:

This example emphasises Fleur Delacour’s exam performance on the Blood and Blood Vessels topic of Edexcel GCSE PE. Fleur has four data points per lesson:

- Number of exam answers written.

- % performance on her most recent answer.

- % performance from all answers including time-restricted and non-time restricted.

- % performance from all time-restricted answers

Can there be any doubt that Fleur needs to write some exam answers on the Components of Blood? Can there be any doubt that Fleur’s most recent answer on the Structure of Blood Vessels was a dip in performance compared to her previous answers? Can there be any doubt that Fleur writes better exam answers for the Redistribution of Blood lesson compared to her classmates?

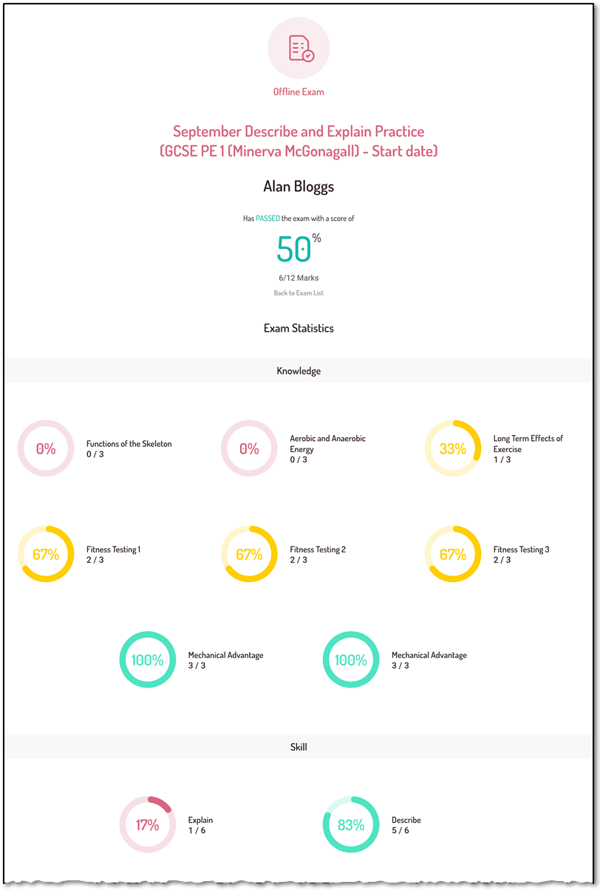

And another example:

Can there be any doubt that Alan needs to revisit his answers on the Functions of the Skeleton and Aerobic and Anaerobic energy lessons? Can there be any doubt that Alan performs better with the describe (AO1) skill than the explain (AO2) skill?

…and let’s look at one more example:

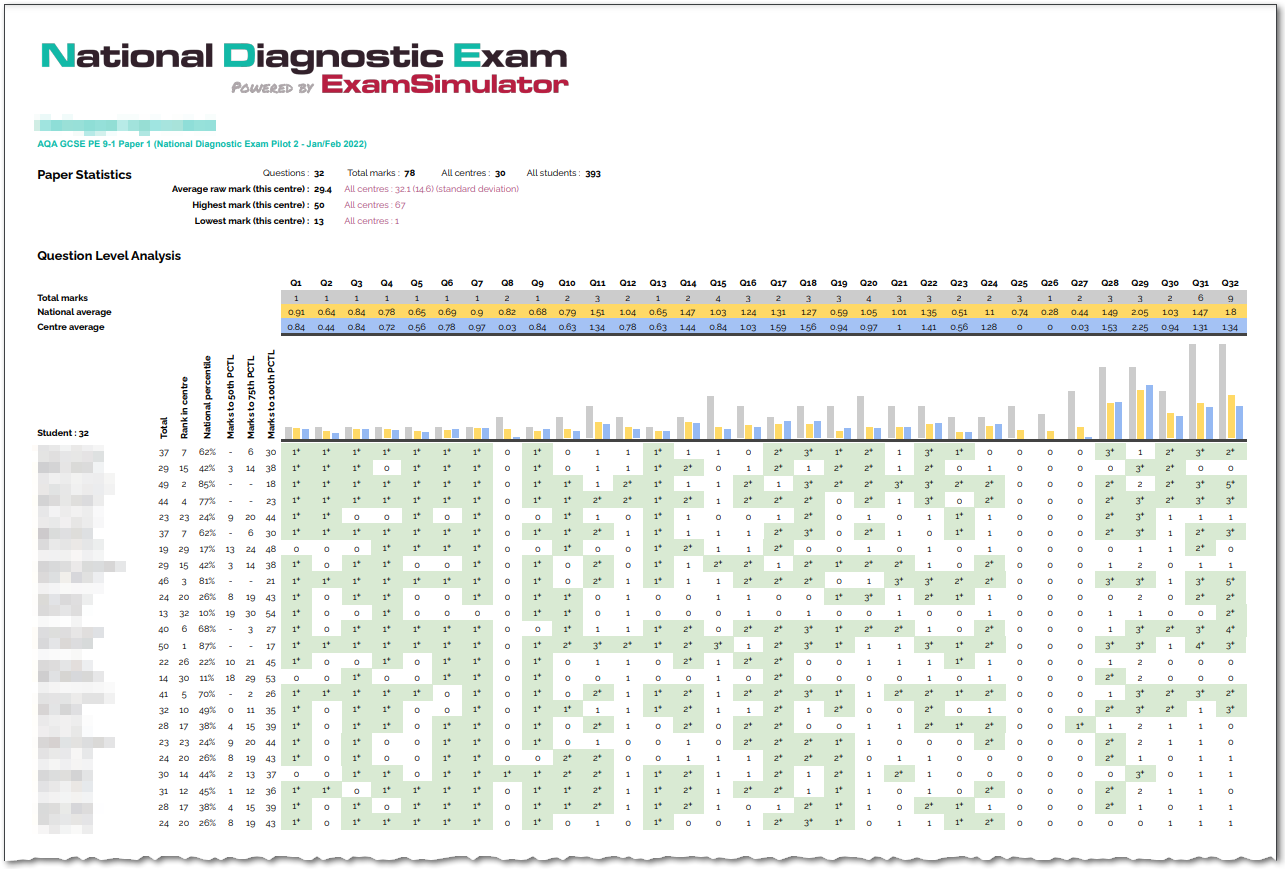

This shot is taken from a National Diagnostic Exam for AQA GCSE PE Paper 1 sat by a school in March 2022.

Can there be any doubt that this cohort of students need to work on their 6 and 9-mark answering skills? Can there be any doubt that the topic area covered in question 8, 12, 15, 25, 26 and 27 are areas of weakness for this cohort?

Learning activities, assessment activities, etc. must be diagnostic.

Thank you for reading this post. I am aware that my writing is challenging and, at times, provocative. I hope that you choose to view this positively and recognise that different voices are a good thing.

Finally, I would be very grateful to receive a comment from you below. I always value comments and always answer them.

Have a great day.

%20Text%20(Violet).png)