James's PE classroom rules: Part 2

Last week, I started writing about my ten PE classroom rules and got to rule 5 ⤤. This week, I want to expand to my remaining five rules to give you a picture of how I work. All of these “rules” are written with a non-zero-tolerance approach. There are always exceptions to the rules but I hope they may give you an insight into a few ideas and, perhaps, also into why PE teachers might experience some of the things they do when teaching.

Last week, in Part 1:

- Straight lines. ⤤

- No arrows unless we are drawing vectors. ⤤

- Label, label, label! ⤤

- Perform like it before we write like it. ⤤

- Every example follows the E-I-O model. ⤤

In Part 2:

James’s rule 6: I’m not your nanny.

Right, this one is much more nuanced than you may expect. I am not establishing a rule of meanness here. I’m establishing a rule of ownership. These are the things I (almost) never do for my students:

- The photocopying

- Giving permission to go to the toilet

- Taking in work

- Setting homework

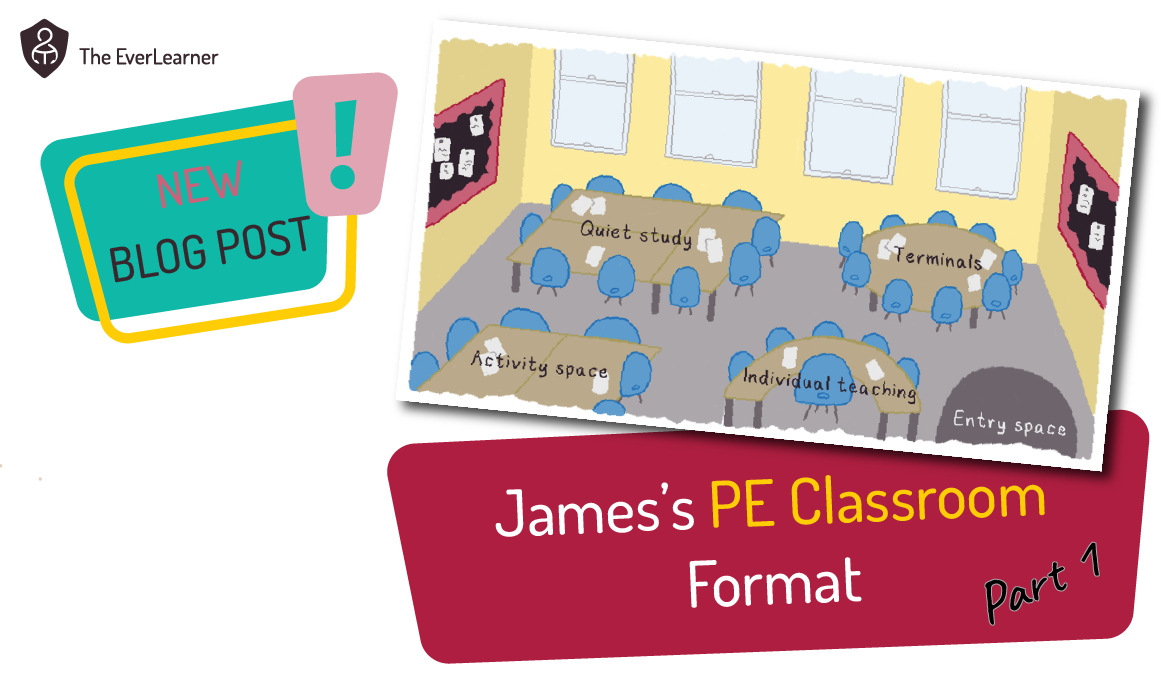

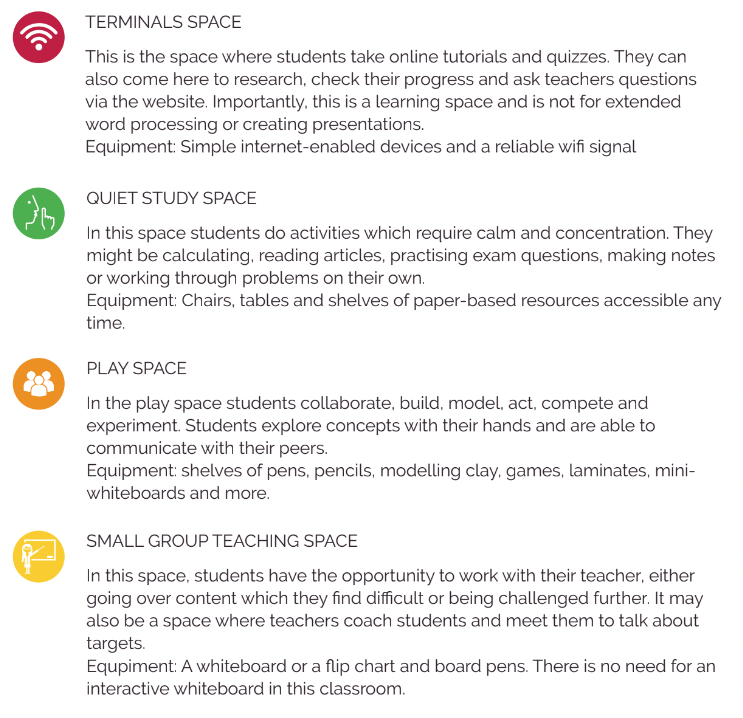

All of this needs context. My classroom is probably not like yours: my classroom is decentralised. 🤯 In general terms, my classroom works like this:

- All skills and content are established in (typically) two-week chunks.

- All resources are available to the students from the start of this two-week period.

- All students agree to and work towards targets over this two-week period.

- All tasks are set at the standard of mastery except any “data extraction tests”.

- Every two-week period culminates with a highly specific assessment.

Therefore, leading up to any two-week period, my “work” has already been done and my concurrent time is spent supporting and reviewing with students. This also means that I am delegating all other responsibilities to the learners.

You may read this and be shocked. You shouldn’t be. What I have described above is a very robust learning environment, developed over years of refinement that works. In fact, I will go further:

Uff! That’s a big claim and you, rightly, may wish to challenge me on it. Watch this space because I am working on producing and reporting the relevant data in due course.

In conclusion to Rule 6, “I’m not your nanny” is not about meanness or aloofness. On the contrary, it is a natural outcome of a well-designed and considered educational environment where the central value is maximising learning. This is all I mean. When you operate a classroom like this, everyone (including both the students and the teachers) is on the same team.

By the way, I used to “tour” this classroom. In 2017, I spent a week presenting the classroom to rooms full of PE teachers who became my students for 90 minutes as I taught a lesson. Perhaps I should reignite this and tour again in 2024. 🤔 Watch this space...

James’s rule 7: Never be silent.

Back in the day when I was a fresh and young PE teacher (later biology and German too), I read a study that claimed that secondary school students heard messages like “Be quiet”, “Stop doing that”, “Sit still”, “Cease doing x, y or z” five times more frequently than they would hear learning messages such as “It was right/wrong because…”, “If you try it this way, you might find…” or “Try this next because…”. I can’t locate that research any longer, so if anyone has access to it, please send it my way. But my overall point and rule is this:

When a student has something relevant to say, they absolutely must say it.

This consideration is at the heart of my classroom. Why? Because my classroom considers “teaching” to be completely secondary to “learning”. Learning is the classroom’s aim. Whether “teaching” happens is irrelevant. Therefore, students voicing things really matters and this includes feedback to me about the classroom.

You should also remember that my classroom is framed around mastery and the successful meeting of targets. Therefore, a lot of what students need to say is about those targets (all of which are individual tasks). Students MUST say these things because meeting those (task-level) mastery targets is the nutrition –or the central value– of the classroom I have set up.

My classroom is not a free-for-all. It is rigorous and robust but it also enables and even causes students to voice their experiences, opinions, needs and suggestions by design. Therefore, my rule is simple: NEVER BE SILENT (when you have something relevant to say)!

James’s rule 8: Errors are good.

If an error occurs in your classroom, what does it mean? What happens after the error? Everyone will have different answers to this question but here’s mine:

Learning –real learning– is always preceded by confusion and/or errors.

Think this claim through a little bit. I am claiming that learning (not repetition/regurgitation/answering a question correctly) is ALWAYS preceded by “a negative”. It is always preceded by being unsure or confused or by an error. Learning is doing something new or differently and these experiences must involve errors of some kind. Therefore, errors are a key element in a true classroom.

I want to ask you a question: do your students ever get frustrated if they make an error? Mine do sometimes, by the way. I am in the real world, like you. But what does that frustration mean at its core? It means that the student is striving to be right or correct or an equivalent and anything other than this is seen as failure rather than feedback. This is not the aim of my classroom. The aim of my classroom is to maximise learning and for them to be “right” in the exam. Between now and the exam, they will perform and receive feedback… perform and receive feedback… perform and receive feedback until “right” emerges in a robust, skill-enabled way.

One of my most formative moments in a classroom was when I noticed a student of mine, Laura, celebrate something when on a computer. Laura was probably my highest-performing-ever PE student. One of those who was getting an A* from day one. I caught her once celebrating a wrong answer in a quiz and I asked her “What happened?” She said back “I got one wrong… Now I know what I need to do.”

This moment has stayed with me. My job as the teacher is to endlessly cause “errors” in a highly supportive environment where feedback and progress are very highly valued.

Don’t get me wrong, no errors in my classroom damage confidence, in my opinion. They are road signs directing the learner and me down the new pathway. To almost quote Andy Dufraine (Tim Robbins) in the Shawshank Redemption: “✽Errors are a good thing… maybe the best of things…”.

✽I substituted hope for errors.

James’s rule 9: There is (almost) zero wriggle room.

Students need to meet their targets. That’s it in a nutshell. Nothing more. Once targets are set and agreed, students meet them. There is no wriggle room.

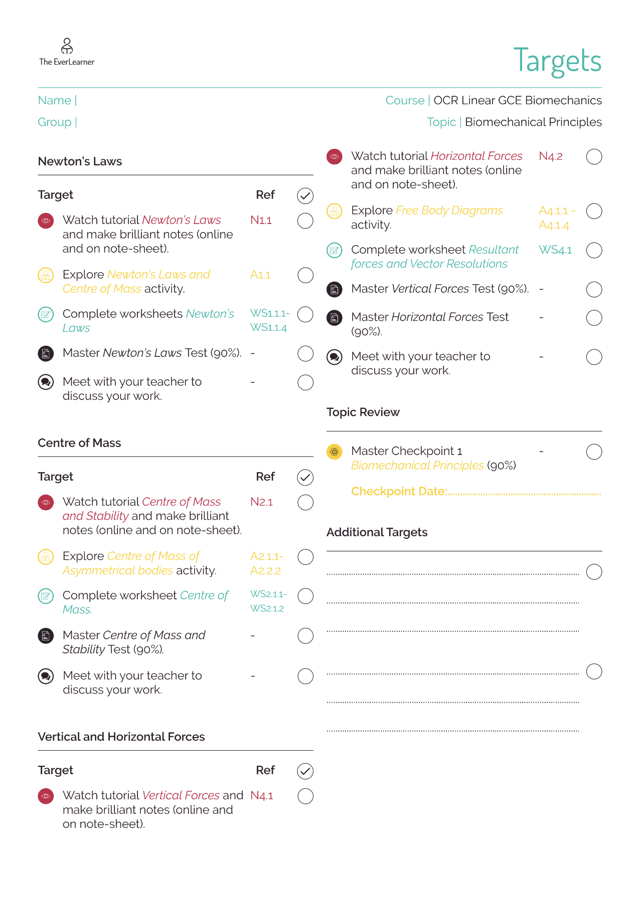

You probably think I’m being pretty harsh with this but, in practice, I’m not. Take a look at some targets and you might see what I mean:

The targets above would span a two-week period consisting of approximately six hours of classroom time. My point is this: with my unwavering support of the student, they must meet these targets. And you know what? They do. Every single time, human beings fill the space that is created for them. And my job is to maximise this space and then scaffold that journey. In a nutshell, that is how I see my job.

James’s rule 10: Yet.

Consider these all too familiar exchanges:

Student

Student James

James Student

Student James

James Student

Student James

James

Notice something from this –somewhat false– exchange: I will not allow the students to not believe in themselves. I am going to (✽appropriately) love them so hard that I will maintain belief in them even if they don’t. I will never, ever accept that they “can’t”. I will always show the student that my belief and –yes!- expectation is that they will get there but also notice that I am available to them to help solve the challenge.

✽At the heart of education is love. Appropriate love. Another term for this could be unwavering belief in the young person in your care.

This is education, my friends. This is what it looks like. This is what it reads like. This is what it means to educate. Education is not just a technical process of the mind. It happens first in the heart and if you want to be an educator (and I mean, a true educator) you have to believe in them. This is why “yet” is the strictest of all rules in my classroom.

By means of a little challenging thought, the flip-side of the “yet”-coin is “still”. I often ask my students to “show me you can still do that.” Doing it once is often not enough. Repeated experiences are often a positive way to enhance the storage and utilisation of knowledge and skills. Those of you who teach or study skill acquisition or sports psychology will know this as Thorndike’s law of exercise.

Conclusion

There you have it, my friends: the 10 rules of my classroom. I am not asking you to agree with me. You may well not. That’s cool! We are all different. But I hope that by reading my “rules” you have got a sense of my work and how I see my job.

Finally, in order to challenge you once more, the 10 rules detailed this week and last are not written down anywhere. There is no policy for this stuff. The rules are in my behaviours, in what I do. They are in my language when I speak with students. They are contained in every interaction I have with the other teachers in my department or with colleagues in the staff room. They are, in essence, who and what I am as an educator. I am extremely proud to share them with you.

Thank you for reading.

James

%20Text%20(Violet).png)