School Assumptions… School Revelations

I remember it really well: It was my first time walking into a GCSE PE classroom as a teacher in my NQT year and I had a strange mix of feelings such as responsibility, fear and trepidation. I looked around the classroom at the Centre Site of my first school employer in Oxfordshire (I’m not going to name the schools as I haven't let them know in advance that I would be mentioning them) and questions streamed across my mind. Why is that there? Why is there an “interactive” whiteboard at the front? Why are students in rows?... From my very first professionally qualified (I had taught classroom PE in my PGCE placements) exposure to a PE classroom, I was asking fundamental and even philosophical questions. I don’t remember having many answers, but I definitely had questions.

I then spent approximately a quarter of a century as a secondary school teacher, middle and senior school leader and, now, continue to work in and with schools and colleges as a business owner of an educational company and school consultant. In all of these roles, there have been huge assumptions made by the institutions that I have worked within about all manner of things and within this post, I want to share how I perceive some of these factors.

Before I write this, I want to communicate that I do not consider myself correct in what follows. These are a series of perspectives that I hold. I’m confident that many readers will disagree with me. This is to be encouraged. It is, in fact, healthy that your opinion is different to mine. Disagreeing is good, right? Dialogue and discourse lead to reflection, in my opinion. But I also hope that you may read my thoughts with an open mind and ponder what I have to say.

Here goes:

The classroom

I mentioned classrooms already in my introduction above. If I were to ask you (presumably a teacher) why learning has to occur in a classroom (I include drama studios, music rooms and gymnasia as classrooms), what would you say? If I were to ask you why French, say, was to be learned in a classroom, what would you tell me?

It is my contention that classroom learning is an assumption, and I would like to reveal why I believe this. As far as I can tell, schools as a whole and, therefore, classrooms, have been structured in such a way that is economically sustainable IF learning is stimulated by some kind of broadcast teaching. There are two elements to this:

- Economically sustainable means that in the UK and other developed countries, ratios of one teacher to approximately 25 learners is –just about– affordable. State education is able to fund the number of teachers and standard resources it takes to teach in a 1:25 structure.

- Broadcast teaching means that one teacher needs to teach approximately 25 students by means of centralised instruction or lecture or “from the frontness”. In other words, the teacher within the 1:25 ratio needs silence for all 25 students to hear their descriptions, explanations and presentations.

It’s important to stress that element 1 is very hard to shift. It would not be appropriate for me to suggest hugely greater education-sector costs through smaller ratios, nor to suggest that we cut costs by increasing the number of students per teacher. So, let’s assume that these economics persist.

However, point 2 is different. Broadcast teaching does not necessarily mean that learning is happening in a classroom. I mean, broadcast teaching often causes some one-pace-fits-all learning if it is done well (I hope that I have done it well the thousands of times I have done it) but, the structure of having a room, separated from others because silence is needed for those 25 + 1 people, is not set in stone. It can be changed. We absolutely do not need to assume that “classes” need to be “(broadcast) taught” in “batches of 25ish” by “one teacher”. These are all assumptions. These assumptions can all be challenged.

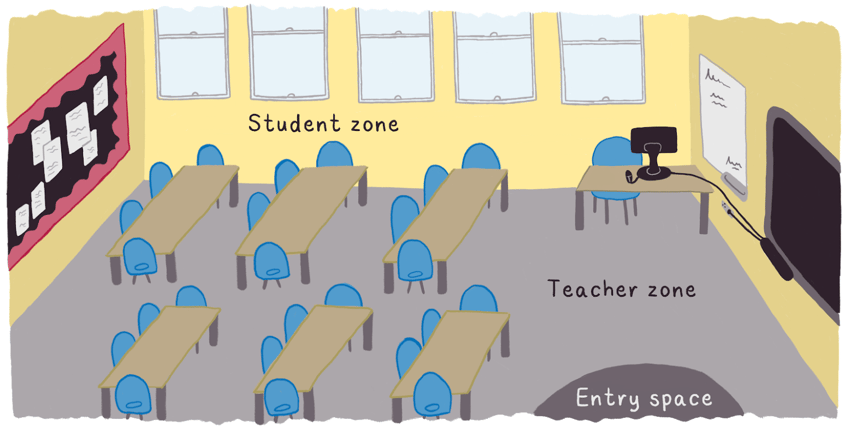

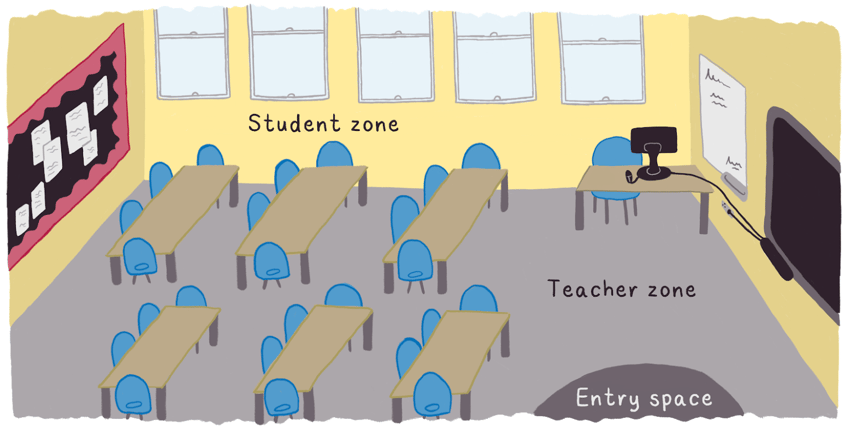

The teacher zone and student zone of classrooms

Most (not all) classrooms are defined by a teacher zone and a student zone.Teacher zones generally contain:

- One teacher

- One computer

- One desk

- One chair

- One whiteboard/blackboard/chalkboard

- One projector or presentational screen

- Many desks

- Many chairs

- Some kind of thoroughfare

Why?

Why?My contention is that what you can see above is analogous to a cinema.

Teacher zone:

- Screen

- Actor

- Guidance such as rules and expectations

- The show!

- Audience

- Recipients

- Passive participants, at least much of the time.

This is exaggerated when teachers broadcast their teaching to the group. This is VERY cinema-ish. Think about the last film you went to see at the cinema. Mine was Longlegs, a horror film with Nicolas Cage. I watched it at an Everyman theatre just outside London and it scared me to bits. The filming was spectacular, the music was moody and foreboding, the acting was shockingly good (and bad, at times). I remember the outline of the story, some of the key moments and one or two lines of script. However, if I were to claim that the “knowledge” of the film had been transferred to me in order to allow me to redeliver or explain or write about it with confidence, I would be lying. Reflect on this, please. “Cinema-classroom experiences” are very unlikely to cause deep, sustained learning.

This is why we do activities, right? Imagine I had watched Longlegs and then done some worksheets or discussed the film. I believe this would help me to retain more understanding. But how is this classroom set up to achieve that?

My contention is that the standard classroom is set up for the least important and most passive aspects of a learning cycle…

…and……the more important, active aspects of learning, where students become agents rather than recipients of their experience, are devalued or restricted because of the room structure.

You will have noticed this in your own teaching when you bravely decided to move the desks or to all go outside or come to the front or whatever.

School rules

Right, which day-to-day rules are most important in your school? Uniform? Not visiting the toilet in lesson time? Queueing? How to enter and exit the school site before and after the school day?

If we take for granted that many rules, such as non-violence, codes of conduct, non-bullying, etc are absolutely correct, what is the function of lower-level school rules, such as, say, not going to the toilet during lesson time?

It is my contention that rules are created and applied as a patch when no solution to a problem can be found. I believe this is the case in all aspects of life.

Before we get into school rules, think about rules in a different environment. Driving rules, for example. Why are there so many rules about what drivers, cyclists and pedestrians can and can’t do? You are probably thinking “To keep people safe” or “To keep traffic moving” or “So everyone drives with approximately the same style”. I believe that these are all superficial reasons and that the deeper reason is something else. Look at this:

What is that missing bit? What is beneath even the good intentions of these rules? The answer is this:

This is actually why we have road rules. We do not have road rules because road rules are inevitable. We have road rules because there is no solution to the fundamental problem of human beings combined with movement and travel combined with perfect safety. Because of this gap, we must have rules (and, by the way, I agree with the rules). But do not assume that the rule is the solution. It is not. The rule exists in the absence of a solution.

So, let’s apply this way of thinking to schools. A school has a rule that students can’t go to the toilet during lesson time without express permission from their teacher. Whilst this seems sensible on the face of it, it also creates all kinds of problems:

- There is indignity in asking to go the loo.

- Some teachers sometimes do not respond positively to the request.

- It can be particularly awkward for females experiencing their menstrual cycles. Asking can be very awkward.

- It can be particularly awkward for some people who experience medical conditions.

Clearly, the rule does not sufficiently solve the fundamental problem, but I wonder whether most teachers recognise what the actual fundamental problem is.

So, the rule is no toilet during lessons. Why? Because students should go on their break, right? Or because the corridors and toilets are not monitored during lesson time, right? Wrong! These are not the fundamental causes. The fundamental cause is that your school, like all the ones I have worked in, expects learning to happen within isolated, mostly quiet classrooms, synchronously no matter what the individual needs, some of which are biological, of our students. That is the problem! Creating the no-toilet-during-lessons rule is the patch that is placed on top of the problem because no solution has been found.

Now, I don’t want to create a utopian or, worse, a nihilistic vision for how schools should structure the rules that they see fit. Rather, I want every reader of this post to acknowledge something. Whether you are an EQT, a headteacher or anyone in between, please acknowledge that the rules that you are applying, often with strict codes and even disciplinary consequences, are absolutely not the solution to whatever problem you are facing. Furthermore, I urge you to look out for messages such as “zero tolerance” when it comes to rules. What I can tell you with confidence is that the colleagues who claim the importance of zero tolerance definitely do not yet have a solution to the problem. Moreover, they are extremely unlikely to have pondered what the actual fundamental problem is. Be very, very cautious to follow the leadership messages of the people who advocate a strategy of zero tolerance.

A little word on zero tolerance

I want to be clear about something: I do judge the message of zero tolerance very negatively in schools. I also try not to judge the people delivering the message. Teachers progress to management and leadership roles with very little training, on average. Therefore, understanding why some colleagues would find zero tolerance as their strategy is understandable.Where I do judge people is when I hear and read of very senior colleagues who define their leadership with zero tolerance messages. Whilst I do not want to name names, there are leaders in our sector making careers on zero tolerance approaches. I have very close to zero (not zero, though!) respect for these colleagues on a professional level. Why? Because there is always an exception. Every rule needs to be bent from time to time. There are frequently individual circumstances that mean that zero tolerance is, quite literally, the worst approach possible. I have a very strict relationship with my students about homework completion. But could you imagine if I held a zero tolerance approach and a year 10 student, say, suffered a bereavement or a legitimate illness or numerous other things? Who would I be if I applied zero tolerance? Rather, I create homework tasks which are “skinny”, “regular” and “impactful” and then create a culture of importance around their role in learning (you can read more about this in my blog "Assignment Wizardry! Setting PE Homework and Class work for Impact - Part 1"). Guess what: my homework responses are very close to 100%. And zero tolerance has nothing to do with it.

SLT

How many of us teachers question the assumptions above? How many of us look at an SLT, say, within a school and ask why so few of them are highly qualified in human learning processes? Why am I probably correct to suggest that in your school, on your SLT, you will probably have a team of people who look something like:- headteacher responsible for strategic planning;

- deputy headteacher responsible for day-to-day operations and student behaviour;

- school business manager;

- school bursar;

- data manager;

- assistant headteacher responsible for T&L but without high-level studies in human learning processes - more likely, they are an experienced and skilled teacher; and

- assistant headteacher responsible for pastoral care.

I am not knocking anyone who holds any of these jobs. I have worked in these roles. People I love are currently doing these roles in more than one institution. But I want to ask: if schools and the education sector are to be “the learning industry”, how can it possibly be the case that a deep understanding of the process of learning is such a marginalised skill set on school SLTs?

Maybe your school is the exception. Maybe every member of your SLT deeply understands the processes of human learning. If this is true, I salute your school. In most cases, the framework I have detailed above is far more likely.

Schools employ managers for finances, systems, strategy, data, student behaviour and so many other things but they seem, infrequently, to employ people who truly understand how human beings learn, remember and forget. Why?

Conclusions

So, there are a few of my opinions for you to ponder. It would be fair to say that I have challenged rather than solved. I did consider writing the details of what I believe the solutions should be in more of this post, but I wish to retain these ideas for potentially future posts.

Thanks for reading. Please do consider commenting. I always reply. 🙂

Have a lovely day.

James

%20Text%20(Violet).png)