Reframing educational assumptions in PE and Sport

I am writing this post in order to challenge any PE teacher or course manager who operates in a qualification-based environment such as GCSE Physical Education, BTEC Sport, Cambridge National or A-level PE course. I want to take eight –perhaps– assumed concepts and challenge them in your mind. Inevitably, this post may come across as critical of the current status quo but, as always, my aim is to provoke and stimulate in the most positive of ways.

Reframing is a classic neurolinguistic programming (NLP) behaviour but, crucially, it is a potentially powerful and enabling principle which may help you reimagine your qualification PE/Sport provision.

I would like you to reframe all of the following concepts:

- ability;

- differentiation;

- assessment;

- feedback;

- teaching;

- lesson;

- specification;

- target grades;

1. Ability

Let’s start here: I invite you to reframe the concept of student ability within your PE course. I invite you to notice if or when student ability is referenced and, potentially, where and when the concept informs decisions. In this post, I will write most forcefully about the concept of student ability and the wholeheartedly negative influence it has on PE teachers and PE students.

I want to define, loosely, what I mean when I write/read or say/hear the word “ability”. In my mind, ability is the assumed biological level of learning potential that a student has. It is permanent and it is enduring. In other words, it means that ability is fixed: there are some “smart kids” and some “less smart kids”. This, to me, is what ability speaks of. Now let me be clear:

"I utterly and wholeheartedly reject the concept of learner ability."

Before you start pointing at the numerous studies on cognitive performance and intelligence in order to disagree with my statement, I want to make something very clear: I don’t care about those studies. I don’t care that the concept of IQ probably does exist. I also don’t care that there is a general societal consensus that some people are brighter than others. I care about one thing and one thing only: performance.

I am asking you to frame the –in my opinion– irrelevant concept of ability with the highly relevant concept of performance.

So, what’s this all about? Why is this writer being so direct about student ability? My answer to this is both philosophical and pragmatic. Let’s look at it philosophically first:

Student learning potential is unknown and unknowable.

The statement I have just written above and that you have just read goes to the heart of my own educational philosophy. Therefore, I am going to write it again:

Student learning potential is unknown and unknowable.

Therefore, some of my "twitchiest" teacher moments have occurred when systems have, quite literally, been structured based on the assumption that a student’s learning potential is knowable. The misuse of target-setting data is a classic example and I will write about this later in this post but, for now, let me be general:

Any school/college system, process or protocol based on the measurement or estimation of student learning potential is utterly flawed.

Let me go further and write a statement directly to you, the reader, who I am assuming is an educator:

You (or I) have absolutely no idea of your (or my) students’ level of learning potential.

Colleagues, please take this in: No teacher has the capacity to measure or estimate their students’ learning potential. You cannot do it! I cannot do it! Any attempt to do it is flawed and will lead to massively generalised responses to massively individualised experiences. Therefore, why are so many school and college systems, processes, protocols and, worse, assumptions based on the premise that we can?

Colleagues, even if you disagree with me, please accept this statement as a fervent opinion by an educator who has worked in the British education system for nearly three decades:

Student ability, whatever that is, has no relationship whatsoever with student performance in courses such as GCSE PE or BTEC Sport, A-level PE, etc.

I realise that most of you will disagree with that statement. All I am asking you to do is to read it and accept that I hold the opinion as strongly as I have represented it here and that my opinion has relevance. I also ask you to appreciate that writing such a statement in a public forum such as a blog is likely to attract derision and, therefore, is a relatively ballsy thing to do. Honestly, I do expect you to disagree with me. Most of my colleagues have disagreed with me about this over the years but I have never, ever seen any evidence that compels me to believe that cognitive ability needs to affect student performance at KS4 and KS5. Moreover, I am very confident that learning potential cannot be measured.

The implications of my position are many. Firstly, I get ostracised on a regular basis. Secondly, it means that I can view students slightly differently from other teachers. For example, I reject all of the following:

- differentiation by task;

- differentiation by outcome;

- assessment of a student (I refer to this common assumption as “spatial assessment”);

- target grades;

- predicted grades;

- prediction tools such as Midyis, KS2 SATS, 11+, etc.

I could go on with this list but, crucially, I want to stress that I view all these processes as educationally invalid.

In the worst cases, educators will use predictive tools such as Midyis, SATS or 11+ as some kind of baseline testing that can provide a flight path of likely student performance. I want to be clear here: If someone provides me with a document or webpage that tells me that test X has provided student Y with score Z and that now, I should be helping them to aim for grade A or B or C or 9 or 7 or 4, I will literally throw that piece of paper in the bin or delete that bookmark from my browser. To anyone that claims that an individual’s KS2 SATS scores can help us to predict their desired or acceptable grade at, say, GCSE, I say this: BULLSHIT! As far as I am concerned, an educator cannot and will not apply population-level data to an individual learner. A true educator can never do this and will never do this!

So, there you have my views on ability. But how do we replace this assumption? The answer to this can be expressed in two ways:

- students performance;

- temporal assessments.

Let’s imagine that you are eight lessons into a GCSE PE course and you offer your students a summary assessment of the eight week’s learning. Let’s say that student X scores 56% on that assessment. What does this mean to you as their teacher? What do you draw from this? Do you quickly reassure yourself that it’s fine because their target grade is a 4 or do you consider them a C-grade student or middle ability or anything equivalent?

In my frame, the only thing that I can be confident in about that assessment is the following:

Student X scored 56% on content and skills Y on day Z.

In other words, my student is offering me a temporal assessment: an assessment of a moment. Any further extrapolation of meaning from this data is flawed. What the student and I have to do is look at all the behaviours that have led to that 56% performance on that day and tweak them to cause improvement in future, equivalent experiences. The cause of the 44% gap in performance will be evident in those behaviours. I guarantee it. If I start to think that their 56% performance is representative of their ability, there is a high chance that change will not occur. There is a high chance that the student will repeat their learning behaviours that led to the 44% gap. The 44% gap was caused not by ability but by learning behaviours or the lack of them.

2. Differentiation

Now that I have got through the concept of ability, you won’t be surprised to read that I reject at least two typically used forms of differentiation in classrooms. They are:

- differentiation by task;

- differentiation by outcome.

Here’s why:

| Type of differentiation | Common behaviour | Why it's flawed |

| By task | Student A gets worksheet X whilst student B gets worksheet Y. | Requires the educator to be able to accurately measure or estimate a student’s learning potential. As already detailed above, no educator can do this. |

| By outcome | Student A has an acceptable passing standard of X%, whilst student B has an acceptable passing standard of Y%. | Requires the educator to accurately predict or estimate a student’s learning potential. As already detailed above, no educator can do this. |

Therefore, you may be thinking that I do not differentiate. Absolutely not. Differentiation is critical in a successful classroom but my contention is that only two forms of differentiation are educationally valid:

| Type of differentiation | Common behaviour | Why it's relevant |

| By pace and/or repetition | Student A can take longer to achieve standard X than student B but both students are expected and scaffolded (see next row) to achieve that standard. | Students can work to the expected standard at a more individual pace, including repeating experiences as required. This “deceilings” performance for all students. |

| By type of scaffold | Student A requires a different type of support to achieve standard X than student B. | Being stuck is fine because support is available and, more importantly, relevant. This form of differentiation demystifies the issue of “stuckness” and “errors” and highlights these experiences as signposts for necessary support. |

If in your classroom, department or school you are encouraged to differentiate by task or outcome, there is a fundamental flaw in the logic that is being applied to that guidance.

So, where does this leave us after two reframes?

3. Assessment

If you have read to this point, you probably already know where I am going with this: It’s important that we reframe assessments from being spatial (assessment of a student) to being temporal (assessment of a moment). Our mentality with regard to assessment and assessment models is that assessments, whether formative or summative, are temporal and are only valid in that specific moment. I feel very strongly about this.

Consider how many times you have heard equivalent phrases to:

Student X is a Y-grade student.

Compared to phrases such as:

Student X scored Y TODAY on content and skills Z.

The latter needs to be our typical methodology. By viewing assessment as temporal rather than spatial we will naturally look to promote change, improvement and growth as well as eliminate any limiting learning behaviours that the student may be displaying. Furthermore, the student will have the ongoing and consistent sense that their teacher believes that they can learn, improve and perform. Seriously, think about this last statement. What does it mean to a student to be categorised as a certain level of learner? To be told “56% on that test is enough”? What must the student internalise based on these messages? What if… what if… what if… the typical message they received was more like “You scored 56% on that assessment today. Now we need to tweak things in order to get that score up. I’m here to support you all the way.”? The power in this mentality, a little like student-learning potential, is unknown and unknowable.

I should stress at this point that in two weeks’ time, I will be posting a whole article about assessment models in PE courses and some of these ideas will be illuminating with more examples and clarification.

So, we are now here:

4. Feedback

Feedback is an absolutely critical feature of any learning programme. Please do not perceive that I am, in any way, attempting to undermine the importance of it. I align tightly with the view of Kirschner that if there is:

No feedback…

...there is...

...no learning.

Feedback is the lifeblood of learning. However, I perceive that many schools are focussing on the wrong variables when it comes to feedback. It seems that many schools have feedback protocols that focus on how to give feedback, how to engage in dialogue with a student, how to structure feedback phrases or even what colour pens to use. Whilst none of these points are irrelevant, all of them will diversify based on the individual student, teacher and course. There is no ideal feedback model.

However, there is one variable related to feedback that is absolutely critical: it is the timing of feedback.

We know –and I really do mean know– that feedback has a greater tendency to cause learning the more proximal it is to the activity. In other words, in order to have the highest probability of causing impact through feedback, the feedback needs to be received as timely as possible after the performance. Therefore, this needs to be the focus of our feedback models and, yes, policies.

So, I am predicting that some readers are feeling pressured by my statements on timely feedback. You’re overworked, right? You can’t do more, faster, right? I totally agree. Therefore, unrealistic expectations about faster feedback are not what is required here. Rather, smart working is the key here. My contention is that timely feedback and sensible working regimes are two sides of the same coin. Timely feedback causes sensible working regimes. This matters.

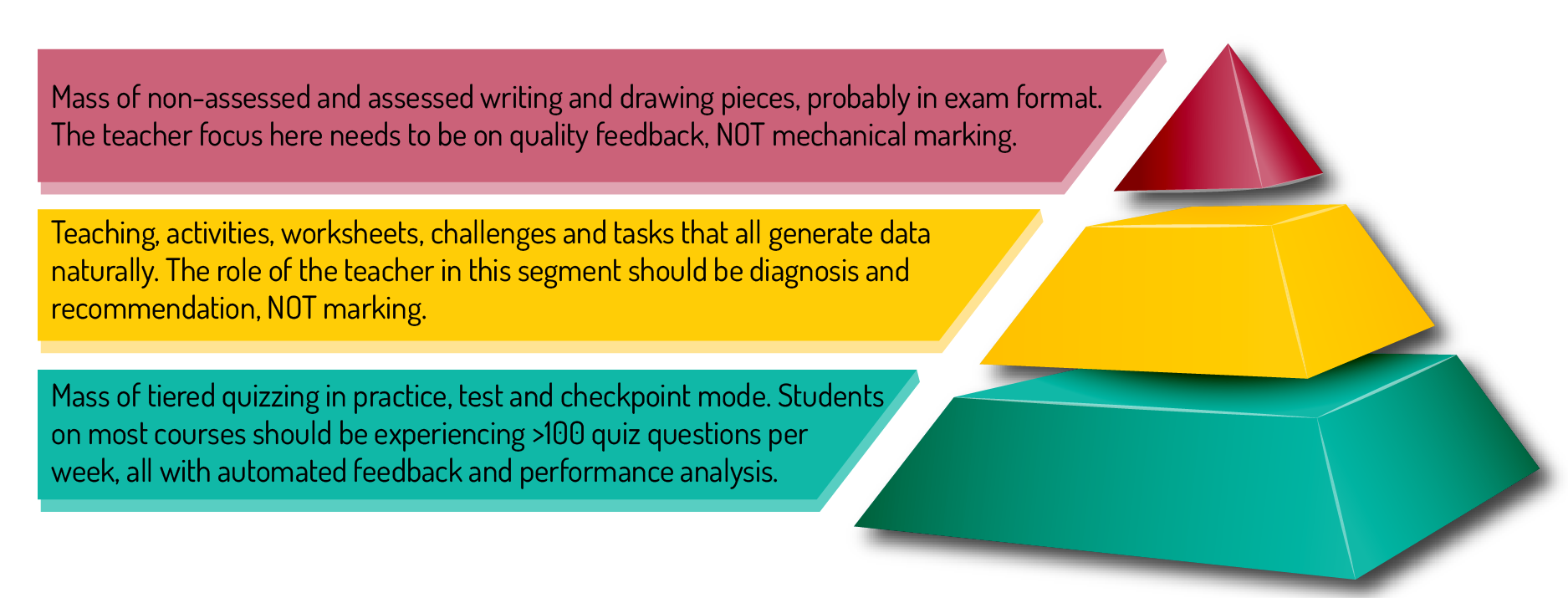

Take a look at this possible feedback pyramid as general guidance with regard to feedback.

I am mindful that some meat will need to be added to these bones and I will aim to publish more formally on feedback in the very near future. But what matters here is the base of the pyramid. The upper sections can only be enabled because we use automation in the base. I am going to make a strong statement here:

PE courses that do not incorporate a mass of automated quizzing with immediate, personalised feedback are now massively out of date.

Your students need to be using machines to quiz now! If they are being denied this opportunity then I can tell you with confidence that other students in other centres are being provided with a far superior educational model.

Furthermore, the automation of the base has massively positive impacts on the teacher who can retain time for the types of feedback that machines are not capable of.

I repeat: I will blog further on this topic but, for now, I want to summarise once again:

5. Teaching

I’m probably going to get savaged for this one and, to be honest with you, I don’t really expect that any PE teacher is going to literally replace the word teaching with anything else. However, by means of a thought experiment, I’m going to ask you to delete the word teaching from your vocabulary until the end of this mini-section. Fair enough?

The aim of teachers should not be to teach but to cause learning. It’s actually irrelevant whether a teacher “teaches”. It is very relevant whether they cause learning. Now, I know what you’re thinking: This is just semantics… teaching and causing learning are the same thing. I want to agree with this perspective but my experiences of three decades in schools tell me otherwise. My belief is that teachers often overfocus on behaviours they summarise as teaching, covering or delivering and often underfocus on behaviours that cause learning such as feedback, repetition or concentration, to name a few. Ponder how many times you have heard a teacher refer to “covering a course.” Now ponder how many times you have heard equivalent conversations about “causing robust and sustainable learning.” The latter conversations do happen, I know, but I am arguing they should be relentless and that they are, too often, not.

If you are a PE course manager or Head of PE, challenge your teams to ponder this provocation. And, what's more, do it over and over again. Whilst I don’t want to be puritanical about these things and disappear into the unrealistic realms of utopia, I am asking you to challenge yourself and your teams to think differently about this concept.

6. Lesson

Oh, man… this one isn’t going to be popular either. I want you to ponder that the concept of a lesson is not particularly helpful. I have written extensively before about the need to rebrand a lesson, at least in our own minds, as the peak learning experience. The concept of a “lesson” promotes the assumption of one-and-done teaching and learning. If we think of a lesson as the peak learning experience, then the natural questions to ask are what happens before and after the peak. This is exactly why the Build-Peak-Maintain model matters and I urge you to read more about it.

In my own thinking, no course actually has “lessons” in the traditional sense. Rather, courses have structured peak learning moments in relation to specific content and skills.

7. Specification

I work extremely closely with exam-board specifications. I know them inside out. I know exactly how they are written and can even interpret the types of conversations that must have occurred to have led them to be written the way they are. Knowing your specification is a critical behaviour for PE teachers and learners.

However, I want to challenge you a little. In my mind, a specification is actually better described as the assessed content (and sometimes skills) of a course. Therefore, it is not all that needs to be learned and, I fear, too many PE teachers perceive the specification to be this.

PE colleagues, please read this statement carefully:

Your PE/Sport specification is absolutely NOT all that your PE students need to learn!

There are so many examples where a specification is not robust enough to be a teaching guide that it frightens me how many teachers use it like one. Let me just choose a couple of them as examples:

There are PE courses in play right now with the following issues that mean we need to spread out from our assessed content:

| Problem | Solution |

| Course that requires an understanding of the antagonistic movement of the ankle but only names the gastrocnemius as operating at the joint. The tibialis anterior is omitted, and, therefore, a true understanding of how the ankle is moved is impossible. | Students need to learn, whether they can name it or not, that the gastrocnemius has an antagonistic pair on the front of the lower leg. |

| Numerous A-level PE courses that require knowledge of changing dissociation levels of oxygen including the Bohr shift but do not require a knowledge of the principle of cooperativity. Without cooperativity, oxygen dissociation and the Bohr shift, literally, cannot be understood. | Make gentle reference to cooperativity as the source principle and encourage a very brief conversation with any A-level biology students within your class about what is occurring. |

| Almost all PE courses omit knowledge of the vertebrae but require knowledge of things such as movement analysis, core stability, functions of the skeleton or posture. | We MUST reference the vertebrae. We cannot teach PE without it. Avoid technical terms by all means but, please, please, help your students to understand the pivotal (little joke) role that the vertebrae play. |

I could go on but I’ll leave the examples there. What is more important to recognise here is the right that our students have whilst on our courses. They have the right –and I really do mean the right– to learn beyond a prescribed assessment content. Whilst I do not encourage wild tangents of learning, I do ask every PE teacher to listen out for intriguing questions that their students might ask and to consider resourcing students with a potential answer. You can read more about this concept in a previous blog post titled “PE teachers, stop teaching to the spec!”

8. Target grades

It feels that I have come full circle from the start of this post when I banged on about ability relentlessly. Target grades are a problem in education. Here is the problem:

Target grades are, too often, used as individual indicators of student learning potential despite them being based on population data.

The use of target data to tell a learner they should aim for grade X is, quite literally, educationally unethical. It is, in fact, disgusting to me. Once again, I need to repeat the core of the educator’s framework:

Student learning potential is unknown and unknowable.

Therefore, target grades based on population averages and then applied to individual children can –to choose my words carefully– go very, very far away from me.

I have found one sound use of target grades in education only. But I fear that if I write it down you won’t believe me. Here goes…

In my last three years as a Head of PE in my penultimate full-time role in schools, I actively sought out students with low target grades and attempted to enrol them onto my course. Just to be clear: I was so confident in the experiences that students were going to receive on our course that it was worthwhile recruiting the lowest-performing students at the centre who had an interest in the subject. Now, I wasn't daft enough to recruit students with no interest in A-level PE. That would have been a folly and, at heart, the wrong outcome for that learner. However, I managed to flip the idea of a “good group” or “good cohort” being one filled with previously successful learners. Our model was so robust that we had utter confidence that students would perform well and, students with lower target grades offered the possibility of massively improving value-added performance of the course.

I really want you to ponder what I have written here. If your course is/was truly world-class, you would/do have the tendency to recruit students with these characteristics:

- lowest target grades; and

- an interest in the subject.

Sure, we love our high GCSE performers coming onto A-level PE or BTEC sport. Of course! But what I am saying here is that world-class educational environments see target grades not as a predetermined flight path for individual achievement but as a cohort-level indicator of where the greatest levels of success might be achieved.

So, what do I personally do with target grades? I toe the line and follow all the protocols that a school/college requires of me as an employee and then I ruthlessly ignore them.

Conclusions

So, there you have it: A bunch of provocative ideas to keep you warm this January. I’m proud of what I have written above. I know that many people will disagree with me. That’s fine and I encourage comments and feedback. My aim is not to be right nor to convince you of anything. Rather, I write these things because colleagues tell me they value them and, whilst that keeps happening, I’m going to keep writing.

Thanks for reading and have a lovely day.

James

%20Text%20(Violet).png)