Differentiation in the PE Classroom

Dear PE teachers.

Before I write this post, I want to make a statement: What follows is not a presentation of all the reading that I have done of countless books and items of research relating to differentiation. In fact, much of the reading I have done would disagree with what I will write below. Rather, what I am sharing today is my personal view about differentiation and the summaries that I have made –personally– after over two decades of classroom PE teaching. I aim to write the post provocatively and to “pull no punches” because I think that this topic really matters. It may be the most important post I ever write.

Terminology

I refer to differentiation as differentiation. Others use the term adaptive teaching. Honestly, I don’t mind which term anyone prefers to use. Use both, use neither… it doesn’t matter. There is no achievement in changing a label for the same set of behaviours (I once worked on an SLT where an entire team of teachers spent months rebranding literacy to “litness” because literacy was deemed to be an intimidatory term for students. Other than that, almost nothing else changed. What’s the point?!). So, my aim today is not to relabel differentiation or adaptive teaching but, rather, to fundamentally challenge the assumptions that teachers make about differentiation or adaptive teaching no matter what it is called.

Types of differentiation

As far as I can tell, there are four main types of differentiation:

- Differentiation by task

- Differentiation by outcome

- Differentiation by pace and/or repetition

- Differentiation by type of scaffolding.

If you consider any specific differentiation behaviour, it will fit into one of these categories. For example, “ability setting” is a structural methodology to achieve differentiation by task and differentiation by pace, perhaps. All forms of differentiation are achieved in one of the four ways above.

So, let’s break them down:

| Type | What is it? | Requirements | Regularity of my usage |

| By task | Providing a different activity for learners of different levels / experience / potential |

Knowledge of a student’s current performance Knowledge of what a student has the potential to learn |

Never |

| By outcome | Providing a different expected standard of outcome for different learners |

Knowledge of a student’s current performance Knowledge of what a student has the potential to learn |

Never |

| By pace and/or repetition | Providing a fixed standard of achievement and allowing different learners different lengths of time or number of repetitions to achieve it | Knowledge of a student’s current performance | Every lesson |

| By type of scaffolding | Providing different support structures to different students in order to meet a standard | Knowledge of a student’s current performance | Every lesson |

My view on all this stuff has been established early in this post. As you can see above, I reject the first two forms of differentiation. I never –maybe I should write “no longer” because I used to– perform differentiation by task or outcome. Never (no longer)!

So, why is this? Why is it that many, many teachers seem to aspire to differentiation by task and outcome and that I reject it 24 years into my teaching career? The answer to this question is relatively simple:

No teacher –me included– has any capacity to know or to measure the learning potential of any student.

To accurately differentiate by task or outcome, a teacher must believe that they know what the student is capable of learning. Worded another way, they must also know what a student is not capable of learning. I know that I don’t know this. Whilst I can’t know for sure that you (a fellow teacher, presumably) don’t know this either, I strongly believe that you don’t. Going further: I strongly believe that no teacher has the capacity to know their students’ learning potential. Why is this? Well, I could be pragmatic and state that there is not a test or task in existence that can reasonably claim to be accurate in measuring learning potential. Or, put more philosophically:

Human learning potential is unknown and unknowable.

If I am right, if human learning potential is unknowable, where does that leave differentiation by task and outcome? In my opinion, it leaves them in the zone of guesswork on the part of the teacher. It requires a teacher to be somewhat demagogic and to expect to know what is the right learning level for a student at any moment. If I know for sure that I definitely can’t do that accurately, why do we as teachers believe that differentiation is achieved this way?

I would actually like to take things further:

Differentiation by task and outcome will feel necessary to PE teachers because, by nature, the system that they are working in is not differentiated. In other words, you may find yourself differentiating not because of the model within which you work but in spite of it.

Most school models revolve around groups (sometimes larger, sometimes smaller) of students doing roughly the same thing, at the same time, at the same pace and moving on to other learning whether they have mastered it or not because others around them are doing that. Why is that?

Step back from all of the assumptions about schools and classrooms and timetables and blah blah blah. Let those ideas go from your mind for just a second and answer this question:

When considering the maximisation of learning only, is it a good idea that all young people within a group (or subgroup) should learn at an average pace, at the same time, with the same time limits applied, typically to a non-mastery standard?

If you remove all your assumptions about costs and school buildings and the teaching profession doing things a certain way for years and all that stuff, what is your answer to that question?

Let’s go even further: Isn’t it true that your (and my) need to differentiate by task and/or outcome is a direct result of the non-personalised educational system in which we operate?

I think it is. And, for this reason, I reject differentiation by task and outcome because both methods are flawed and, in fact, non-educational. I could (although I won’t) even argue they are inhumane.

What if?

There is a real danger of my post becoming a little “pie in the sky” but, regardless, I’m going to keep going.

Consider answering, or at least pondering, these “What if” questions”:

What if…

So, just for now, let’s assume that all of these things were possible. Let’s imagine an enabled rather than disabled classroom. Let’s dream of the actual ideal, not just a slight variation of what has always been.

In the circumstances above, differentiation would only be ethically justifiable based on two variables:

- Time spent and/or repetition of a task

- The type of scaffold a teacher would provide to different learners

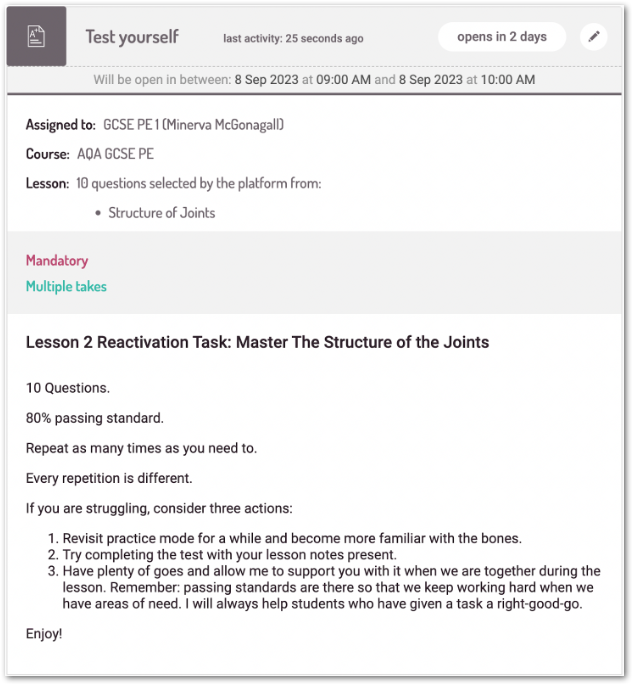

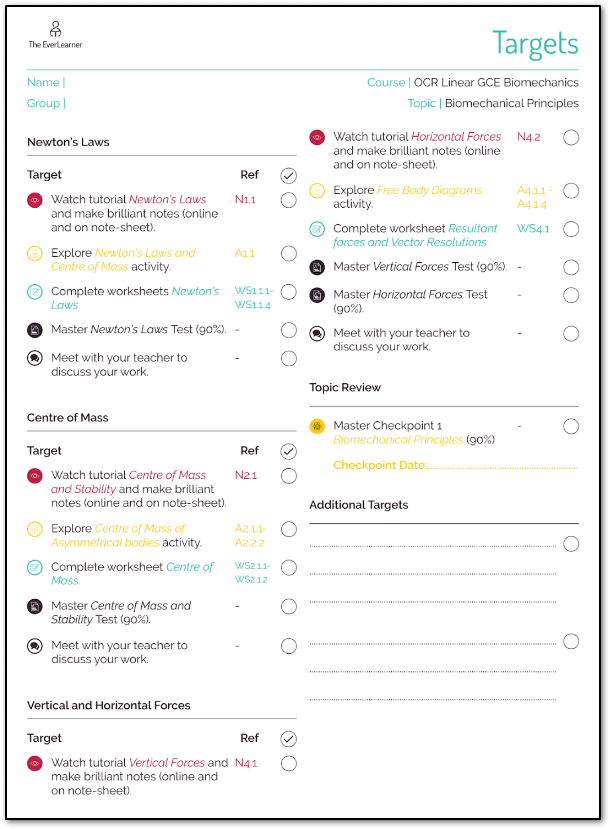

Let me give you some examples. Take a look at this task. The task is short (I use the term “skinny”), has a mastery standard and can be experienced by a student at different rates and repetitions whilst always being rigorous.

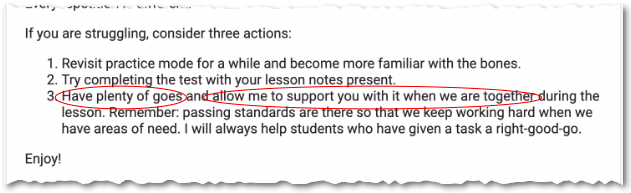

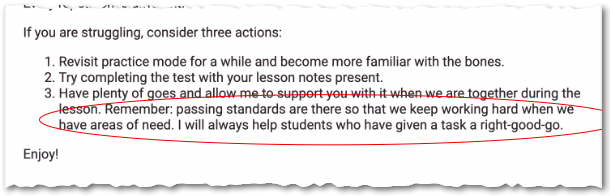

Look closely at the image again and notice the two areas I have circled for you to clarify my point:

And look at the image one more time:

Can there be any doubt about the culture of this task? I want to ask you to step back from one’s assumptions once again. Now, let’s look at another example, this time from different content:

These tasks would span a period of approximately four hours of classroom time as well as home study. Notice that every task is set (for everyone) at a fixed mastery standard but does not compel students to do so in isolation or collaboration, nor does it compel a specific timescale.

Consider these two instructions that a teacher might utter:

Instruction 1: "Here’s your task. Please, aim for a minimum of a grade 4 to pass this task. You have ten minutes."

Instruction 2: "Master this task. Have numerous attempts if necessary and I am here to support you in reaching the standard at any time."

So, what do you think? Which instruction is educationally valid? Which instruction are students most likely to hear in UK schools and classrooms?

If I am right –and you are welcome to think and argue I am not– what does this mean for all of us as teachers?

The big barrier and how to overcome it

Whether you agree with me or not, there are barriers to what I am advocating for. You probably have terms like “time” and “workload” in your mind and these may seem like barriers to achieving what I am describing. “Surely, surely, it can’t be as simple as I am describing.” “Surely, everyone would do it this way if it were so easy.” These are fair observations and colleagues should be reminded that throwing one’s current model out without an alternative means a vacuum will be created.

But, my own personal experiences prove to me –and maybe just me– that there is an alternative and that the alternative is achievable. In fact, that the alternative outperforms every other classroom model by every relevant educational metric.

So what is that alternative? Tune in to my blog next week, when I will be publishing: “James’s PE Classroom Model”, within which I will fully document how I achieve what I am advocating for above.

Thank you for reading.

James

%20Text%20(Violet).png)